We've all heard about the Vikings. Sometimes this word evokes in a person the idea of evil and bloodthirsty people who are dressed in coarse wool, and on their heads they have horned helmets, armed with axes, looking for profit. But in reality everything is different. Who the Vikings really were, where they came from and where they lived, you will find out by reading this article. Everything important about the history of the Vikings is told here.

Vikings - origin story

The term "Viking" comes from the Old Norse word "vikingr". This word is associated with the designation of bays and fjords. In addition, there is a region in Norway called Vik, and some scientists believe that the Vikings began to gather there. The Vikings were ordinary free peasants of Scandinavia. Archaeologists have not found a single “helmet with horns”; this is just a trick by directors to give the Vikings a more bloodthirsty look in films. They lived in groups in villages with small populations. They were a harsh people, because... it was impossible to survive otherwise in Scandinavia. While vassal-suzerain relations began to develop in Europe and castles were built, this was not the case in Scandinavia, all peasants were free and worked for themselves.

The Viking customs were very interesting. So, if a child was born, he was immediately taken out naked into the street in order to show the baby to nature to his mother. From childhood, children were trained in military affairs, because the Scandinavian tribes were often at enmity with each other. After reaching the age of sixteen, young men were taken to an “obstacle course” that they had to complete within a certain time and then fight an adult member of the tribe. If a young man passed the test successfully, he received warrior status and was allowed to marry. As for the family, the Vikings lived in big house the whole family. The concept of family included not only parents, but also sons and their families. Children from siblings were considered relatives to each other. If one brother died, the other was to marry his wife and take the children.

Vikings - history of conquest

Conditions for survival in the north were not the best, which prompted northern peoples to travel and conquest. Initially, the Viking campaigns were aimed at finding new lands to live in, but over time they began to raid the settlements of Britain and Northern Europe. However, first things first.

Viking ships

In order to cross the seas, the Vikings needed suitable ships. And they had such ships. Often the name of the ship of the militant Vikings appears in crosswords and scanwords - they were called “Drakkars”. The name of the ships on which the Vikings traveled was given in honor of dragons, mythical creatures that the Vikings respected and believed that they existed and could bring good luck to sailors, and they installed a dragon statue on the bow of the ship. The Drakkar was an excellent ship for that time. Narrow and long, with a wide bottom, it could reach a length of up to 60 meters and a width of 5 to 12. Such a ship was propelled by a sail or oars. On such a ship it was convenient not only to sail across seas, but even across oceans. If you are wondering how to draw a Viking ship, then the answer is simple: look at the thematically relevant illustrations on this page. You'll immediately get an idea of what these rugged ships looked like.

The first Viking raid occurred in 789. Three ships sailed to South-West England, attacked the settlement of Dorset and plundered it. This date is considered to be the starting point of the Viking expansion. The Vikings were pagans, and often began to attack the coastal monasteries of Britain and Northern Europe. They killed the monks, took out all the jewelry and their conscience did not torment them. Over time, the people of Scandinavia realized that robbery was quite profitable, and the number of Vikings increased, and the territory of their expansion expanded. In 839, the Norwegians founded their kingdom in Ireland, and in 844 they reached the shores of Muslim Spain. In the same year, Cordoba, the capital of Muslim Spain, was captured and partially plundered. In 845 Paris was captured. After 15 years, the Vikings Askold and Dir became princes in the city of Kyiv, and in the same year the Vikings appeared under the walls of Constantinople. This was the apogee of their expansion; all of Europe knew and feared the Vikings. Nowadays, many people confuse the concepts of Normans, Vikings and Varangians. In fact, everything is very simple - in northern Europe and Italy the Vikings were called Normans, in Rus' and Byzantium Varangians. Thus, in Rus' and Byzantium, the courage and fighting skills of the Varangians were highly valued, and the rulers of these states had personal Varangian guards. Over time, the Vikings would conquer England, create their own states in northern France and southern Italy, and become rulers of Russian lands.

Some geographical discoveries of the Vikings

However, the Vikings were not only engaged in robbery and robbery, but also discovered new lands for themselves. So, in 860 the island of Iceland was discovered. Several colonies were built on it, which over time grew greatly, the largest population numbering 40,000 people. Soon the Vikings sailed to Greenland, and then to the shores of North America. There they began to try to found colonies (around the year 1000), but the distance from the main lands of residence, the harsh climate and poor relations with the indigenous American peoples forced the Vikings to abandon this idea. Despite this, it was the Vikings who were the first to reach America, and not Christopher Columbus.

In England, the Vikings were called ascemanns, that is, sailing on ash trees (ascs). since the upper plating of Viking warships was made of this wood, or by the Danes, regardless of whether they sailed from Denmark or Norway, in Ireland - by Finngalls, i.e. “light foreigners” (if we were talking about Norwegians) and oakgalls - “dark foreigners” (if we were talking about the Danes), in Byzantium - Varangs, and in Rus' - Varangians. - Note translator

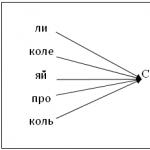

The origin of the word "Viking" (víkingr) still remains unclear. Scientists have long associated this term with the name of the region of Norway Vik, adjacent to the Oslo Fjord. But in all medieval sources the inhabitants of Vik are called not “Vikings”, but differently (from the words vikverjar or vestfaldingi). Some believed that the word "Viking" comes from the word vík - bay, bay; Viking is the one who hides in the bay. But in this case, it can also be applied to peaceful merchants. Finally, they tried to connect the word “Viking” with the Old English wic (from the Latin vicus), which meant a trading post, a city, a fortified camp.

Currently, the hypothesis of the Swedish scientist F. is considered the most acceptable. Askeberg, who believes that the term comes from the verb vikja - “turn”, “deviate”. A Viking, according to his interpretation, is a person who sailed away from home, left his homeland, that is, a sea warrior, a pirate who went on a quest for prey. It is curious that in ancient sources this word was more often used to describe the enterprise itself - a predatory campaign - than the person participating in it. Moreover, the concepts were strictly separated: trading enterprise and a predatory enterprise. Note that in the eyes of the Scandinavians the word “Viking” had a negative connotation. In the Icelandic sagas of the 13th century. Vikings were people engaged in robbery and piracy, unbridled and bloodthirsty. - See: A. Ya. Gurevich. Viking campaigns. M., Nauka, 1966, p. 80. - Note translator

More precisely, the quote from Tacitus is set out in the book “Germany”, published in the series “Literary Monuments”: “...Rugia and Lemovia (near the Ocean itself); distinctive feature of all these tribes - round shields, short swords and submission to the kings. Behind them, in the midst of the Ocean itself, live communities of Swions; In addition to warriors and weapons, they are also strong in the fleet. Their ships are remarkable in that they can approach the berth at either end, since both of them have the shape of a bow. Swions do not use sails and do not attach oars along the sides in a row one after another; they, as is customary on some rivers, are removable, and they row them as needed, either in one direction or the other.” - Cornelius Tacitus. Op. In 2 volumes. T. 1. L., Nauka, 1969, p. 371. - Note reviewer

The construction of the Danish Wall lasted for three and a half centuries (from the beginning of the 9th century to the 60s of the 12th century). This shaft, 3 m high, 3 to 20 m wide, stretching across the southern part of Jutland from the Baltic to the North Sea, served Danish troops for defense purposes back in the Danish-Prussian War of 1864 - Note reviewer

The information given here and below regarding the number of fleet and military force Vikings are known from the conquered. Since defeat from a numerous and correspondingly strong enemy affected the honor of the vanquished less, inflated figures have reached us. At the same time, those under attack could hardly distinguish the Norwegians from the Danes. The reason for this was the language, which only at that time began to be divided into Norwegian and Danish-Swedish. - Note author

Stones with runes, of which there are about 2,500 in Denmark alone, were placed in 950–1100. in memory of the fallen. According to Ruprecht's research, a third of these cenotaph stones were placed on the territory that ended up abroad: the dead Vikings for the most part were young and died a violent death during the campaigns. Let us give examples of texts: “King Svein (Forkbeard) set a stone for Skarbi, his warrior, who went west and found his death near Khaitaba.” “Nafni erected this stone for his brother Toki. He found death in the west." “Tola installed this stone for Guyer, his son, a respected young warrior who died on western route Vikings." - Note author

The huge tapestry, 70 m long and 0.5 m wide, contains more than 70 scenes. - Note translator

In the 11th century In addition to England, the Normans captured Sicily and Southern Italy, founding here at the beginning of the 12th century. "Kingdom of the Two Sicilies". The author mentions exclusively the aggressive and military campaigns of the Danes and Norwegians and says nothing about the Swedes, whose expansion was aimed mainly at Eastern Europe, including Rus'. - For more details, see “World History.” In 12 volumes. M., Gospolitizdat. T. 1, 1957; A. Ya. Gurevich. Viking campaigns. M., Nauka, 1966. - Note translator

The decisive battle between Harald and his opponents in Hafrsfjord took place shortly before 900, and therefore there was no direct connection between the migrations to Iceland and political events in Norway. - Note translator

Currently, there are about forty hypotheses about the location of Vinland. Equally not indisputable is the hypothesis of the Norwegian ethnologist H. Ingstad, who in 1964 discovered the ruins of a settlement in Newfoundland, which he identified as Vinland of the Normans. A number of scientists believe that this settlement belongs to the Eskimo Dorset culture. Moreover, in the sagas the climate of Vinland is assessed as mild, which does not correspond to the harsh subarctic climate of Newfoundland. - Note reviewer

During archaeological excavations in Greenland in 1951, a fragment of a device was found, which is considered a direction-finding card (wooden compass) of the Vikings. The wooden disk, believed to have 32 divisions along the edge, rotated on a handle passed through a hole in the center and, being oriented relative to the cardinal directions (by the rising or setting of the Sun, by the shadow at noon, by the rising and setting of certain stars), showed the course. - Note translator

Interesting information about Oddi is provided by R. Hennig: “The history of Icelandic culture knows of a certain strange “Star” Oddi, who lived around the year 1000. This Icelander was a poor commoner, a farm laborer for the peasant Thord, who settled in the deserted northern part of Iceland near Felsmuli. Oddi Helgfasson fished for Tord on the island. Flatey, and being completely alone in the vast expanse, used his leisure time for observations, thanks to which he became one of the greatest astronomers that history knows. Engaged in tireless observations of celestial phenomena and solstices, Oddi depicted the movement of celestial bodies in digital tables. In the accuracy of his calculations, he significantly surpassed the medieval scientists of his time. Oddi was a remarkable observer and mathematician, whose amazing achievements have only been appreciated in our days.” - R. Hennig. Unknown lands. M., Foreign publishing house. Literary, 1962, vol. III, p. 82. - Note translator

It could also be an Iceland spar crystal, in which, when bearing on the Sun, two images appeared due to the polarization of light. - Note translator

The author, speaking about the navigational knowledge of the Vikings, is mistaken. It is unlikely that the Vikings determined the coordinates to find their place. They probably only had rough maps, similar to future portolans, with a grid of only directions. The portolans themselves, or compass maps, as is known, appeared in Italy at the end of the 12th - beginning of the 13th century; the use of nautical charts with a grid of latitudes and longitudes dates back only to the 16th century. Back then, to get from one point to another, you only needed to know the direction and approximate distance. The Vikings could determine the direction (without a compass) during the day by the Sun, using a gnomon (especially knowing the points of sunrise and sunset during the year), and at night by the Polar Star, and the distance traveled - from the experience of sailing.

The Portuguese Diego Gomes first determined latitude from the Polar Star during a voyage to the coast of Guinea in 1462. Observations for this purpose of the greatest height of the Sun began to be carried out ten or twenty years later, since it required knowledge of the daily declination of the Sun.

Sailors began to independently determine longitude at sea (without reckoning) only at the end of the 18th century.

This does not mean, however, that the Vikings did not control their location on the high seas. O. S. Reuter (O. S. Renter. Oddi Helgson und die Bestiminung der Sonnwenden in alten Island. Mannus, 1928, S. 324), who dealt with this issue, believes that the “solar board” used for this purpose was a rod , installed on board the ship in a vertical position, and by the length of the midday shadow from it falling on the jar, the Vikings could judge whether they adhered to the desired parallel.

It's not hard to imagine how this could happen. The Vikings sailed in the summer, but the declination of the Sun on the day of the summer solstice (now June 22) is 23.5°N, and for example, a month before and after this day - 20.5°N. Bergen is located at approximately 60° N. w. Therefore, to adhere to this latitude, the height of the Sun at noon on the day of the summer solstice is H=90°-60°+23.5°=53.5°.

Consequently, with a solar board length of 100 cm (according to Reiter), the length of the shadow should be 0.74 m and, accordingly, a month before and after the solstice - 82.5 cm. Thus, it was enough to have these marks on the bank so that the Vikings in midday we checked our position. - Note translator

They belonged different peoples, but understood each other perfectly. They were united by many things: the fact that their homeland was the northern limit of the earth, and the fact that they prayed to the same gods, and the fact that they spoke the same language. However, what united these rebellious and desperate people most firmly was the thirst for a better life. And it was so strong that almost three centuries - from the 8th to the 11th centuries - entered the history of the Old World as the Viking Age. The way they lived and what they did was also called Viking.

The word "Viking" comes from the Old Norse "vikingr", which literally translates as "man from the fjord". It was in the fjords and bays that their first settlements appeared. These warlike and cruel people were very religious and worshiped their deities, performing cult rituals and making sacrifices to them. The main god was Odin - the Father of all Gods and the God of those killed in battle, who after death became his adopted sons. The Vikings firmly believed in the afterlife, and therefore death did not frighten them. Death in battle was considered the most honorable. Then, according to ancient legends, their souls ended up in the wonderful country of Valhalla. And the Vikings did not want any other fate for themselves or for their sons.

The overpopulation of the coastal regions of Scandinavia, the lack of fertile lands, the desire for enrichment - all this inexorably drove the Vikings from their homes. And this was only possible for strong warriors who could easily endure hardships and inconveniences. Detachments were formed from Vikings prepared for battle, each of which consisted of several hundred warriors, unquestioningly obeying the clan leader and the king-prince. Throughout the Viking Age, these units were entirely voluntary.

During the battle, one of the warriors always carried the clan banner. This was an extremely honorable duty, and only a chosen one could become a standard bearer - it was believed that the banner had miraculous powers, helping not only to win the battle, but also to leave the bearer unharmed. But when the enemy’s advantage became obvious, the main task for the warriors was to preserve the life of their king. To do this, the Vikings surrounded it with a ring and shielded it with shields. If the king did die, they fought to the last drop of blood next to his body.

Berserkers (among the Scandinavians, a mighty, frantic hero) were especially fearless. They did not recognize armor and marched forward “like madmen, like mad dogs and wolves,” terrifying the enemy troops. They knew how to put themselves into a euphoric state and, breaking through the front line of enemies, dealt crushing blows and fought to the death in the name of Odin. Battle-hardened Vikings typically won victories both at sea and on land, earning them the reputation of being invincible. Everywhere, heavily armed detachments acted in approximately the same way - their landings took cities and villages by surprise.

This happened in 793 on the “holy” island of Lindisfarne off the east coast of Scotland, where the Vikings plundered and destroyed the monastery, which was considered one of the largest centers of faith and a place of pilgrimage. Several other famous monasteries soon suffered the same fate. Having loaded their ships with church goods, the pirates went out to the open sea, where they were not afraid of any pursuit. Just like the curses of the entire Christian world.

A quarter of a century later, the Vikings assembled a large force to attack Europe. Neither the scattered island kingdoms nor the Frankish empire of Charlemagne, which had weakened by that time, could provide them with serious resistance. In 836 they sacked London for the first time. Then six hundred warships besieged Hamburg, which suffered so badly that the episcopate had to move to Bremen. Canterbury, secondarily London, Cologne, Bonn - all these European cities were forced to share their wealth with the Vikings.

In the fall of 866, ships with twenty thousand soldiers landed on the shores of Britain. On the lands of Scotland, the Danish Vikings founded their state Denlo (translated as the Strip of Danish law). And only 12 years later the Anglo-Saxons regained their freedom.

In 885, Rouen fell under the onslaught of the Normans, then the Vikings again besieged Paris (it had already been plundered three times before). This time, about 40,000 soldiers landed at its walls from 700 ships. Having received compensation, the Vikings retreated to the northwestern part of the country, where many of them settled permanently.

After decades of robbery, the uninvited northern guests realized that it was more profitable and easier to impose tribute on the Europeans, since they were happy to pay off. Medieval chronicles testify: from 845 to 926, the Frankish kings paid the pirates about 17 tons of silver and almost 300 kilograms of gold in thirteen stages.

Meanwhile, the Vikings moved further south. Spain and Portugal were subjected to their raids. A little later, several cities on the northern coast of Africa and the Balearic Islands were plundered. The pagans also landed in western Italy and captured Pisa, Fiesole and Luna.

At the turn of the 9th - 10th centuries, Christians discovered weaknesses in the Vikings' combat tactics. It turned out that they were incapable of long sieges. By order of the king of the Franks, Charles the Bald, the rivers began to be blocked with chains, and fortified bridges were built at their mouths; deep ditches were dug on the approaches to cities and palisades were erected from thick logs. In England, around the same time, they began to build special fortresses - burghs.

As a result, pirate raids increasingly ended in disaster for them. Among others, the British king Alfred managed to dispel the myth of their invincibility by fielding taller ships against the “sea dragons,” which the Vikings could not board with their usual ease. Then, off the southern coast of England, two dozen Norman warships were destroyed at once. The blow dealt to the Vikings in their native element was so sobering that after it the robbery began to noticeably decline. More and more of them abandoned Viking as an occupation. They settled on the captured land, built houses, married their daughters to Christians and returned to peasant labor. In 911, the Frankish king Charles III the Simple granted Rouen and the surrounding lands to one of the leaders of the northerners, Rollon, honoring him with the ducal title. This region of France is now called Normandy, or the Land of the Normans.

But the most important turning point of the Viking Age was the adoption of Christianity by King Harald Bluetooth of Norway in 966. Following him, under the growing influence of Catholic missionaries, many soldiers were baptized. Among the last pages of the Viking military chronicle is their seizure of royal power in England in 1066 and the enthronement of the Norman Roger II to the throne of the Kingdom of Sicily in 1130. Rollo's descendant, Duke William the Conqueror, transported 30,000 warriors and 2,000 horses from the continent to Albion on 3,000 ships. The Battle of Hastings ended with his complete victory over the Anglo-Saxon monarch Harold II. And the newly-made knight of the Christian faith, Roger, who distinguished himself in the crusades and battles with the Saracens, with the blessing of the Pope, united the Viking possessions in Sicily and southern Italy.

From the raids of small pirate detachments to the conquest of royal power - the path of the warlike northerners from primitive savagery to feudalism fits into such a framework.

Viking ships

Of course, the Vikings would not have gained their gloomy glory if they had not possessed the best ships of that time. The hulls of their “sea dragons” were perfectly adapted to sailing in the choppy northern seas: low sides, gracefully upturned bow and stern; on the stern side there is a stationary steering oar; painted with red or blue stripes or checks, rough canvas sails on the mast were installed in the center of the spacious deck. The same type of merchant and military ships, much more powerful, being inferior in size to the Greek and Roman ones, were significantly superior to them in maneuverability and speed. Time really helped to evaluate their superiority. At the end of the 19th century, archaeologists found a well-preserved 32-oared dragon in a burial mound in southern Norway. Having built its exact copy and tested it in ocean waters, experts came to the conclusion: with a fresh wind, a Viking ship under sail could develop almost ten knots - and this is one and a half times more than Columbus's caravels during the voyage to the West Indies... through more than five centuries.

Viking weapons

Battle axe. The ax and poleaxe (double-edged ax) were considered the favorite weapons. Their weight reached 9 kg, the length of the handle was 1 meter. Moreover, the handle was bound with iron, which made the blows delivered to the enemy as crushing as possible. It was with this weapon that the training of future warriors began, so they all wielded it perfectly, without exception.

Viking spears were of two types: throwing and for hand-to-hand combat. Throwing spears had a short shaft length. Often a metal ring was attached to it, indicating the center of gravity and helping the warrior to give the throw the right direction. Spears intended for land combat were massive with a shaft length of 3 meters. For combat combat, four to five meter long spears were used, and in order for them to be liftable, the diameter of the shaft did not exceed 2.5 cm. The shafts were made mainly of ash and decorated with applications of bronze, silver or gold.

Shields usually did not exceed 90 cm in diameter. The shield field was made of one layer of boards 6-10 mm thick, fastened together, and covered with leather on top. The strength of this design was given by the umbo, handle and rim of the shield. The umbon - a hemispherical or conical iron plaque that protects the warrior's hand - was usually nailed to the shield with iron nails, which were riveted on the reverse side. The handle for holding the shield was made of wood according to the principle of a rocker, that is, crossing inner side The shield was massive in the center, and became thinner closer to the edges. An iron strip, often inlaid with silver or bronze, was placed on it. To strengthen the shield, a metal strip ran along the edge, nailed with iron nails or staples and covered with leather on top. The leather cover was sometimes painted with colored patterns.

Burmas - protective chain mail shirts, consisting of thousands of intertwined rings, were of great value to the Vikings and were often passed down by inheritance. True, only rich Vikings could afford to have them. The majority of warriors wore leather jackets for protection.

Viking helmets - metal and leather - had either a rounded top with shields to protect the nose and eyes, or a pointed top with a straight nose bar. Overlay strips and shields were decorated with embossing made of bronze or silver.

Arrows VII - IX centuries. had wide and heavy metal tips. In the 10th century, the tips became thin and long and with silver inlay.

The bow was made from one piece of wood, usually yew, ash or elm, with braided hair serving as the bowstring.

Only wealthy Vikings, who also possessed remarkable strength, could have swords. This weapon was very carefully kept in a wooden or leather sheath. The swords were even given special names, such as the Tearer of Chainmail or the Miner.

Their length averaged 90 cm, they had a characteristic narrowing towards the tip and a deep groove along the blade. The blades were made from several iron rods intertwined, which were flattened together during forging.

This technique made the sword flexible and very durable. The swords had guards and pommels - parts of the hilt that protect the hand. The latter were equipped with hooks that could be used to attack by moving the enemy's main blade to the side. Both guards and pommels, as a rule, had regular geometric shapes, were made of iron and decorated with copper or silver plates. The decorations of the blades, extruded during the forging process, were simple and represented either simple ornaments or the name of the owner. Viking swords were very heavy, so sometimes during a long battle it was necessary to hold it with both hands; in such situations, the enemy's retaliatory blows were repelled by the shield bearers. One of the common fighting techniques depended entirely on their skill: they positioned the shield in such a way that the Viking sword did not stick into its surface, but slid along and cut off the enemy’s leg.

History of mankind. West Zgurskaya Maria Pavlovna

Who are the Vikings?

Who are the Vikings?

Nowadays, we call the Vikings the medieval seafarers who were natives of the lands where modern Norway, Denmark and Sweden are located.

The origin of the word “Viking” is a mystery to scientists. The earliest version associates it with the Viken region in southeastern Norway. Allegedly, “Viking” once meant “man from Vik,” and later this name spread to other Scandinavians. However, in the Middle Ages, the inhabitants of Vik were not called Vikings, but vikverjar or vestfaldingI (from Vestfold, the historical province in the region of Vik).

Another theory is that the word "Viking" comes from the Old English wic. Here we see the same root as in the Latin word vicus. This was the name of a trading post, city or fortified camp. At the same time, in 11th-century England, the Vikings were called ascemanns - people sailing on ash trees (ascs), since the hull of their ships was made of ash.

According to the Swedish scientist F. Askeberg, the noun “Viking” comes from the verb vikja - “turn”, “deviate”, that is, a Viking is a warrior or pirate who left home and went on a quest for prey. Indeed, the Viking from the Icelandic sagas is a pirate.

Another hypothesis, which has many supporters to this day, connects the word “Viking” with vi’k (bay, bay). But opponents of this hypothesis point out a discrepancy: there were also peaceful merchants in the bays and bays, but, unlike the robbers, no one called them Vikings.

In Spain, the Vikings were known as "madhus", meaning "pagan monsters". In Ireland they were called Finngalls (“light strangers”) when referring to the Norwegians, or Dubgalls (“dark strangers”) when referring to the Danes. The French called the intrepid sea robbers “people from the north” - Norsmanns or Northmanns. But no matter what they are called, everywhere in Western Europe The Vikings have earned a bad reputation.

Invincible dragons and berserker werewolves

“Almighty God sent crowds of fierce pagans - Danes, Norwegians, Goths and Suevians; they devastate the sinful land of England from one coast to another, kill people and livestock and spare neither women nor children,” as it is written in one of the Anglo-Saxon chronicles. Troubles began on English soil in 793, when the Vikings attacked the island of Lindisfarne and plundered the monastery of St. Cuthbert.

In 83–86 there was no escape from the Vikings - they devastated the southern and eastern coasts of England. It happened that up to 30 Danish longships approached the shore at the same time. Cornwall, Exeter, Winchester, Canterbury and even London suffered from their raids. But until 851 the situation was still tolerable - the Vikings did not winter in England. In late autumn, burdened with booty, they went home.

It must be said that for quite a long time the “fierce pagans” did not dare to move far from the shore - at first they made their way into the interior of the island only about fifteen kilometers. But the brave and bloodthirsty Vikings terrified the British so much that they themselves gave the invaders every chance of success - it seemed that the Vikings had no point in resisting. In addition, ships of sea robbers suddenly appeared on the horizon and reached the shore with lightning speed.

What did the famous longships look like, and why are they called that? They are first mentioned in Tacitus's "Germania". We are talking about the boats of the Viking ancestors, which had an unusual shape. The Arab Ibn Fadlan also has a description of the drakkars. Images of famous ships are preserved in the tapestry of Queen Matilda, wife of William the Conqueror. However, it was possible to see the sea “monster” alive only in 1862, when excavations were carried out in the swamps near Schleswig. The bow and stern of the ship were the same - this amazing design allowed the Vikings to row in any direction without turning around. Several more ships were discovered a little later. Among them, the most famous finds are considered to be the longships from Gokstad (1880) and Ouseberg (1904).

Scientists have reconstructed Scandinavian ships. They established that the drakkars had a keel, to which frames made of the same wood were attached. The drakkar's plating was done cut to pieces. It was attached to the frames using pins, and the boards were connected to each other with iron nails. To seal the seams between the boards, the Vikings used a kind of gasket - a resin-impregnated cord made of pig bristles or cow hair, twisted into three threads. Medieval shipbuilders made rowlocks in the upper part of the plating.

Viking ships reached 30–40 meters in length and sailed. The only sail - red and white striped - was most often made of wool. The drakkar was not controlled using a rudder. It was replaced by a huge oar. In total there were from 60 to 120 oars.

The ship was called Drakkar because its bow was decorated with a carved figure of a dragon. The Norwegian word "Drakkar" comes from the Old Norse Drage - "dragon" and Kar - "ship". The dragon's gaping mouth frightened opponents, and when the Vikings returned home, they removed the monster's head so as not to frighten the good spirits of their land.

The “raven banner” - a triangular banner with the image of a black bird, which evoked quite understandable associations among enemies - also inspired horror. In Norse mythology, a pair of ravens, called Hugin and Munin, were revered as the birds of Odin. Hugin (in Old Icelandic this means “thinking”) and Munin (from Old Icelandic “remembering”) fly around the world of Midgard and report to Odin about what is happening. However, the raven is not only a wise bird, it pecks at corpses. The raven banner was raised during raids. For example, the valiant ruler of Denmark, England and Norway, Canute the Great, fought under him. If the banner fluttered merrily in the wind, it was considered good omen: means victory is guaranteed. Regardless of what was depicted on the flag under which the drakkar sailed, it was personally embroidered by the wife or sister of the Viking leader.

Viking ships were very fast: the Scandinavians covered the 1200 km that separates England from Iceland in just 9 days. Skilled sailors took into account the nature of clouds and the strength of waves, navigated by the sun, moon and stars, and watched for birds. They installed lighthouses on the coast, which Adam of Bremen called the “mountain of the volcano.”

In addition to longships, the Vikings also built merchant ships. What did the medieval Scandinavians trade?

Drakkar on the Bayeux Tapestry

Weapons, furs, skins and leather, fish, whalebone and walrus bone, honey and wax, as well as, as they say, all sorts of things: wooden and bone combs, silver spears, eye paint. And, of course, slaves. The trading ships were called coggs, knarrs and shnyaks. The bodies of the coggs were round. This type of ship was already known to the Frisians. At low tide, the bottoms of the coggs sank to the bottom and the ships were easy to unload, and when the tide began, the cunning boats floated to the top themselves.

Knarrs were large merchant ships, shnyaks were small and not much different from warships. Their forecastle and quarterdeck were often used as fighting platforms - if enemies attacked, the “peaceful merchants” took the fight. The Vikings often took blacksmith tools and anvils on voyages - this made it possible to repair weapons while on the move.

Real naval battles Viking wars were quite large-scale: for example, 400 ships took part in the battle of Hjerungavåg in Norway. In battle, the longships approached each other side by side and grappled with grappling hooks. The warriors fought on the decks, and the battle continued until most of the crew of one of the ships died: surrender was not accepted. The drakkar of the vanquished was given to the victors, and the Vikings cynically called such a battle “cleaning the ship.”

The Vikings showed no less courage on land than at sea. Their traditional weapons were a sword, axe, bow and arrow, spear and shield. What can we say about the armor of the medieval Scandinavians? The cinematic image of a Viking is a bearded, scantily clad man in a horned helmet. What was it really like? The Vikings wore a short tunic, tight-fitting pants and a cloak, which was secured with a fibula on the right shoulder - such clothing did not restrict movement and made it possible to instantly draw a sword. The Vikings tied their shoes – boots made of soft leather – with belts on their calves. Archaeologist Annika Larsson from Uppsala University, studying fragments of fabrics found during excavations of the ancient Viking city of Birka, made an amazing discovery: “Among Viking clothing, red silk, light flowing bows, a lot of sequins, and various decorations are often found,” she said. According to Larsson, the Vikings initially wore cheerful clothes and, with their colorful attire, were reminiscent of modern hippies. According to the researcher, the Viking costume became strict and ascetic only under the influence of Christian missionaries, who first appeared in Sweden in 829.

Of course, the Scandinavians protected their bodies with chain mail. During military campaigns, they wore birnies - protective chain mail shirts made from thousands of intertwined rings. But not everyone could afford such luxury. Birnies were considered of great value and were even passed down by inheritance. When going into battle, ordinary Vikings wore padded leather jackets, into which metal plates were often simply sewn. The warriors' hands were protected by bracers - leather or with metal plates. And surprisingly, but true: the Vikings did not wear horned helmets.

In fact, Viking helmets were quite different: either with a rounded top and shields to protect the nose and eyes, or with a pointed top like a crest. Helmets with a crest are usually called "Wendel-type helmets". This is a legacy of the Wendel culture, which predates the Viking Age - it dates back 400-600 years. Many ordinary warriors did not wear metal, but leather helmets. The Scandinavians were decorated with plates, shields, and eyebrows made of bronze or silver. Of course, these were not just decorations, but magical images that protected the warrior.

So where did the notorious horns come from? There really is an image of a horned helmet - it was discovered on the Oseberg ship of the 9th century. Such helmets actually date back to the Bronze Age (1500-00 BC). They served as headdresses for priests. Researchers believe that the Vikings could also very well have used them for ritual purposes, but it is impossible to fight in a horned helmet - it is easy to knock it down, only slightly touching it upon impact.

Now there is an opinion that the myth of the “horned” Vikings appeared largely thanks to catholic church. Since the Vikings resisted the adoption of Christianity for a long time and, in addition, often attacked churches and monasteries, Christians hated them, considered them “the devil’s spawn” and, quite naturally, crowned their heads with horns. This ideologically based lie later became established in the public consciousness.

Viking shields were usually made of wood. They were usually painted in bright colors - most often red, which symbolized power (or blood?). Of course, there was also magic here - various patterns and designs on the shields were supposed to protect the warrior from defeat. Shields were worn on the back. When the battle began, the Vikings covered themselves with shields, building an impenetrable wall. And raised shields were considered a sign of peace.

The Vikings treated weapons and armor as living beings, giving them nicknames that were often no less glorious and famous than the names of their owners. So, for example, the chain mail could be called Odin's Robe, the helmet - the Boar of War, the ax - the Wound-Gnawing Wolf, the spear - the Stinging Viper, and the sword could be called the Flame of Battle or the Chain-Tearer.

But it was not only swords, spears and bows that gave the fearless Vikings numerous victories. Skalds - Scandinavian poets and singers - talked about those who were “not bitten by steel.” We are talking about berserkers. The earliest surviving source is Thorbjörn Hornklovi's song about the victory of Harald Fairhair at the Battle of Hafsfjord, which supposedly took place in 872. “The berserkers,” it says, “clad in bearskins, growled, shook their swords, bit the edge of their shield in rage and rushed at their enemies. They were possessed and did not feel pain, even if they were hit by a spear. When the battle was won, the warriors fell exhausted and fell into deep sleep.”

The word "berserker" comes from the Old Norse berserkr and translates as "bearskin" (root ber– means “bear”, while – serkr- this is “skin”). According to legends, during the battle the berserkers themselves turned into bears.

It was the berserkers who made up the vanguard that began the battle. With their very appearance they terrified their enemies. But they could not fight for long - the combat trance passed quickly, therefore, having crushed the ranks of the enemies and laid the foundation for a common victory, they left the battlefield, leaving ordinary fighters to complete the defeat of the enemy.

Berserkers were warriors who dedicated themselves to Odin, the supreme god of the Scandinavians, to whom the souls of heroes killed in battle were sent. According to beliefs, they ended up in Valhalla - the afterlife home of slain warriors. There the deceased feast, drink the inexhaustible honey milk of the goat Heidrun and eat the inexhaustible meat of the boar Sehrimnir. Instead of fire, Valhalla is illuminated by shining swords, and the fallen warriors and Odin are served by warrior maidens - Valkyries. Odin is the patron of berserkers and helped the berserkers in battle. Skald (aka historiographer) Snorri Sturluson writes in “The Earthly Circle”: “One knew how to make his enemies go blind or deaf in battle, or they were overcome by fear, or their swords became no sharper than sticks, and his people went to fight without armor and it was like mad dogs and wolves, bit the shields and were compared in strength to bears and bulls. They killed people, and they could not be taken with either fire or iron. It's called going into a berserker rage."

Modern scientists do not doubt the reality of berserkers, but the question of how they achieved ecstasy remains open today. Some researchers believe that berserkers became people with an active psyche, neurotics or psychopaths who became extremely excited during battles. It was this that allowed berserkers to exhibit qualities not characteristic of humans in the normal state: a heightened reaction, expanded peripheral vision, insensitivity to pain. When fighting, the berserker, with a sixth sense, guessed the arrows and spears flying at him, foresaw where the blows of swords and axes would come from, and therefore could cover himself with a shield or dodge. Perhaps the berserkers were representatives of a special caste of professional warriors who were trained for battles from childhood, devoting them not only to the subtleties of military skill, but also teaching the art of entering a trance, which heightened all the senses and activated the hidden capabilities of the body. However, many researchers suggest that the ecstasy of the berserkers had more prosaic reasons. They could have used some kind of psychotropic drugs - for example, a decoction of poisonous mushrooms. Many peoples know “werewolfism”, which occurs as a result of illness or ingestion. special drugs- the man identified himself with the beast and even copied some of its behavior.

Even their comrades were afraid of Scandinavian werewolves. The sons of the Danish king Knud - berserkers - even sailed on a separate drakkar, since other Vikings were afraid of them. These unique warriors could only be useful in battle, and they were not adapted to peaceful life. Berserkers posed a danger to society, and as soon as the Scandinavians began to move on to a calmer life, the berserkers found themselves out of work. And therefore, from the end of the 11th century, the sagas call berserkers not heroes, but robbers and villains to whom war has been declared. At the beginning of the 12th century, the Scandinavian countries even had special laws aimed at combating berserkers. They were expelled or killed without pity. Superstitious fear prompted them to kill berserkers almost like vampires - with wooden stakes, since they are invulnerable to iron. Few of Odin's warriors adapted to their new life. They were supposed to accept Christianity - it was believed that faith in the new God would save them from battle madness. Some of the former military elite even fled to foreign lands.

But in the 9th–11th centuries, when the Vikings on high-speed longships terrified the peoples of Europe, berserkers were still in honour. It seemed that no one could resist them. Big cities, the Scandinavians devastated towns and villages in a matter of days. Not a single coastal country was spared from the “fierce pagans.” In the 30-50s of the 9th century, the Norwegians attacked Ireland. According to ancient Irish chronicles, in 832 Turgeis captured first Ulster, and then almost all of Ireland and became its king. In 84, the Irish finally managed to get rid of the hated ruler - Turgeis was killed. And yet Ireland remained the prey of the Norwegians. The Vikings fought for it among themselves - to the Danes the island also seemed like a tasty morsel. At some point, the Danes managed to come to an agreement with the Irish, but in 83, the Norwegian Olav the White captured Dublin and created his own state on these lands, which existed for more than two hundred years. So Dublin became a springboard from which the Norwegians moved further into the western regions of England.

But the Danes decided to take revenge and in the fall of 86, according to the sagas, they landed on the east coast of England. The brave Vikings were led by Ivar the Boneless and Halfdan, the sons of the legendary Ragnar Lothbrok, and the father of this scion of the Yngling family was called, in turn, Sigurd the Ring. Time has not preserved reliable information about whether such a person really lived on earth, but the sagas tell that the famous military leader received his nickname (Ragnar Hairy Pants) thanks to an exotic amulet - pants that his wife personally sewed. There is another legendary version: as a child, he fell into a snake’s den, but remained unharmed due to the fact that the snakes did not bite through the leather “pants” he was wearing. However, the snakes still destroyed the king: in 86, he, led by his army, invaded Northumbria, but King Ella II defeated him and threw him into the snake well. Ragnar's sons avenged their father: on March 21, 867, Danish warriors defeated the British in battle, King Ella II was captured and given a painful execution. They cut his ribs on his back, spread them apart like wings, and pulled out his lungs. Most historians question this terrible story: most likely, such an execution did not exist - this is what ritual mockery of the corpses of enemies looked like. But be that as it may, Western England came under the rule of the Norwegian Vikings, and Eastern England - the Danish.

The Danes held out until 871, when Alfred the Great came to power, the first of the kings of Wessex, who used official documents title "King of England". Everything ingenious is simple: after many years of unsuccessful struggle with the Vikings, Alfred realized that the Scandinavians preferred naval battles, and ordered the fortresses to be rebuilt. In 878 he won a major land battle and drove the foreigners from Wessex. The Danish leader Guthrum was baptized. However, the invaders remained on the lands of England, and by the end of the 9th century, the “Area of Danish Law” - Denlo - existed on the map. Only in the 10th century did it submit to the power of the English kings. But in 1013, during the reign of Ethelred the Hesitant, whose name speaks for itself, England was invaded by the army of the Dane Svein Forkbeard (Norway by this time was already under the rule of the Danes). Svein was not called Forkbeard because of the shape of his beard: his mustache resembled a fork. Svein quickly captured English cities and villages, and only at the walls of London did the Danes suffer heavy losses. But London eventually capitulated: the Vikings surrounded it, Ethelred fled to Normandy, and the national assembly - the Witenagemot - proclaimed Svein king. Just weeks later he died, and power was inherited by his son Knut, who managed to keep the country in obedience. However, in 1036, after the death of Cnut, the throne went to Svein's grandson. The new king, Hardaknut, caused general disapproval with his exorbitant greed. He imposed such taxes on the Anglo-Saxons that he forced many to flee into the forests. Relations between the vanquished and the victors became tense, but in 1042, during a feast on the occasion of the marriage of the standard-bearer, Hardaknut raised a cup for the health of the newlyweds, took a sip and fell dead. The Anglo-Saxons were saved, and power returned to the old Anglo-Saxon dynasty: the son of Ethelred the Hesitant, Edward the Confessor, became king. And in 1066, England was captured by William the Conqueror, a descendant of the Dane Hrolf the Pedestrian, who founded the Duchy of Normandy in France, the lands of which the Scandinavians first came to in the 9th century, during the reign of Charlemagne. “I foresee how much harm these people will do to my successors and their subjects,” said the powerful emperor - and he was not mistaken. After his death, the state collapsed and the rulers were mired in civil strife. No one could resist the “dragons” anymore, and the Vikings entered the Seine and Loire. They ravaged Rouen, robbed famous monasteries, killed monks, and turned ordinary people who were captured into slaves.

Bronze plate of the 13th century. with the image of a berserker warrior

French chronicles say that around 80 the Vikings, led by Hastings, approached the walls of Nantes. They subdued him and set him on fire. The victors set up camp near the fallen Nantes and from there raided cities and monasteries throughout France. The Vikings sailed to Spain only for a short time, but, having suffered a fiasco there, they returned and attacked Paris. They plundered the city, and King Charles the Bald fled to the monastery of Saint-Denis. The Scandinavians knew no mercy, but they were hampered by the unusual climate of France. The invaders were overwhelmed by the heat and the fruits, which they ignorantly ate green. The exhausted Vikings demanded that the king pay them tribute and, having received a considerable amount of silver, finally left. But not for long…

Soon, Hrolf the Pedestrian, or Rollon, the son of Rognvald, who had been expelled from Norway, appeared in Northern France. On the seashore, Hrolf swore that he would die or become ruler of any land he could conquer. He fought bravely, and in 912, by the Treaty of St. Clair, the French King Charles the Simple ceded to him part of Neustria, between the Epte River and the sea. This is how the Duchy of Normandy, that is, the country of the Normans, appeared. The determined Hrolf was still weaker than Karl, and he set a condition for him: to recognize himself as a vassal of the king and accept Christianity. Hrolf was baptized and received a bonus - the hand of Karl's daughter Gisela. Then the Viking married Pope, the daughter of another king - Ed, who was succeeded by Charles the Simple. She became his second wife - after the death of Gisela. Hrolf distributed land to his comrades, whose number grew as more and more new troops arrived from the north. Many Normans adopted Christianity following the example of their ruler. The descendants of the Vikings quickly learned the French language, but the blood of their warlike ancestors made itself felt for a long time - this is evidenced by the history of medieval Europe.

Already in the 9th century, France became a springboard from which it was convenient for the Vikings to move further south. Around 860, under the leadership of Hastings, they tried to conquer Rome. However, before Eternal City The Vikings did not get there, mistaking Lunks for him. The inhabitants of Lunx were well armed, and the city itself was fortified. Seeing that it was difficult to take the fortress by force, Hastings resorted to cunning. He sent an ambassador to Lunx, who was ordered to deceive the bishop and the count, the owner of the castle: they say that his master is dying and asks the townspeople to sell food and beer to strangers. And most importantly, he wants to become a Christian before his death. The treacherous Hastings was indeed carried on a shield to the city church, where the bishop baptized him. The next day, ambassadors arrived in the city again: now they asked to bury Hastings in church land and promised rich gifts for this.

The gullible bishop agreed and destroyed Lunks: all the Vikings accompanied the imaginary dead man - they must say goodbye to their leader! He was lying on a stretcher in full military armor, but this did not bother the bishop - after all, Hastings was a warrior during his life. The funeral procession, accompanied by the city's top officials, headed to the temple, where the bishop buried the adventurer. When the “body” began to be lowered into the grave, Hastings jumped up from the stretcher. The “Cold Corpse” hacked to death both the bishop and the count. The Vikings captured Lunks. But Hastings wanted to conquer Rome! The ships, loaded with booty, set off again, but the Vikings never reached Rome - they were stopped by a strong storm. To save their lives, the robbers threw their loot overboard. They even considered slaves to be ballast, and the beauties were swallowed up by the depths of the sea.

Hastings's campaign ended ingloriously, but two hundred years later the Scandinavians were already in charge of Italy. First, in 1016, a small detachment of Norman pilgrims returning from the Holy Land helped the Prince of Salerno defeat the Saracens. The Italians marveled at the courage of the Vikings and began to invite them to their service. The Scandinavians “fit” into the Italian landscape and even founded a small Norman possession. And in 1046, the Norman Robert Huiscard arrived on the Apennine Peninsula. From Old French, Robert's nickname translates as Cunning or Crafty. “He was nicknamed Huiscard, because neither the wise Cicero nor the cunning Ulysses could compare with him in craftiness,” his biographer, the Norman chronicler William of Apulia, wrote about Robert. The sixth son of Tancred Gotvilsky, he followed his older brothers to Italy. In 1050–1053, Robert stayed in Calabria, where the Normans fought with the Byzantines and, in addition, under the command of the Cunning, they robbed monasteries and peaceful inhabitants. The tribesmen respected Robert and after the death of his brother Humphred, bypassing the legal heir - Humphred's son, they proclaimed Guiscard Count of Apulia. Moreover, for the annual tribute and promise of help, Pope Nicholas II recognized Robert as duke. The Pope confirmed for him, as a vassal of the Holy See, power over the countries of Southern Italy, which he had already conquered and which he would conquer in the future. Huiscard conquered all of Apulia and Calabria, and in 1071 Bari, the last refuge of Byzantine rule, fell. Robert's brother, meanwhile, took Sicily from the Saracens. Robert's power frightened the new pope, Gregory VII. He excommunicated Huiscard in 1074, but made peace with him in 1080, seeking protection from Emperor Henry IV. Having lifted his excommunication, the pope gave Robert all his possessions as fief, including Salerno and Amalfi, which he had reoccupied. In 1081, the indomitable Robert went on a campaign against the Byzantine Empire. He defeated Alexius Comnenus at Durazzo and reached Thessaloniki. He repaid the Pope with kindness: in 1084, Robert took Rome, sacked it and freed Gregory VII, whom Emperor Henry IV imprisoned in the Castel Sant'Angelo. Together with the Pope, Huiscard retired to Salerno and again began a war with Byzantine Empire. Robert defeated the combined Byzantine-Venetian fleet at Corfu and went to the Ionian Sea, but died on the island of Cephalenia. Huiscard's possessions were divided among his sons: Bohemund received Tarentum, and his father's namesake Robert received Apulia. In 1127, Apulia united with Sicily, and the Norman dynasty ruled the Kingdom of Sicily until the 90s of the 12th century. And Norman blood also flowed in the veins of the Hohenstaufen dynasty that replaced it.

The Rurikovichs also considered themselves descendants of the Scandinavians - the Varangians. But the question of who the Varangians are is still open.

Princes of the Russian land?

The first mentions of varanks, verings or varangs (words consonant with the Russian “Varyag”) date back to the 11th century. So, around 1029, the famous scientist from Khorezm Al-Biruni wrote: “A large bay in the north near the Saklabs is separated from the ocean and extends close to the land of the Bulgars, the country of the Muslims; they know it as a sea of warlocks, and these are the people on its shore.” In the Icelandic sagas the word vaeringjar appears - this is the name of the Scandinavian warriors who served the Byzantine emperor. As we remember, the Vikings fought with the Byzantine Empire, but their amazing strength and courage served as an excellent advertisement for them, and the same Byzantines willingly hired northern warriors. The Byzantine chronicler of the second half of the 11th century, Skylitzes, also writes about the “varangs”: in 1034, their detachment fought in Asia Minor.

In the legal code of Rus' - “Russian Truth”, dating back to the reign of Yaroslav the Wise (1019–1054), the status of certain “Varangians” is defined. Modern researchers most often identify them with the Scandinavian Vikings. However, there are other versions of the ethnicity of the Varangians: they could be Finns, German-Prussians, Baltic Slavs or people from the Southern Ilmen region. Scientists do not have a consensus about the origin of the Varangians themselves or their name. But the most sore point is the legendary calling of the Varangian princes to Rus'.

There is the so-called “Norman theory”, whose supporters consider the Scandinavians to be the founders of the first states of the Eastern Slavs - Novgorod, and then Kievan Rus. They refer to the chronicles, which say that the tribes of the Eastern Slavs (Krivichi and Ilmen Slovenes) and Finno-Ugrians (Ves and Chud) decided to stop civil strife and in 862 turned to some Varangian-Russians with a proposal to take the princely throne. Where exactly the Varangians were called from is not directly stated in the chronicles, but it is known that they came “from across the sea,” and “the path to the Varangians” lay along the Dvina. Here is an excerpt from “The Tale of Bygone Years”: “And the Slovenians said to themselves: “Let us look for a prince who would rule us and judge us by right.” And they went overseas to the Varangians, to Rus'. Those Varangians were called Rus, just as others are called Swedes, and some Normans and Angles, and still others Gotlanders, so are these.”

From the chronicles it is known what names the Varangians-Rus had. Of course, these names are written down as they were pronounced East Slavs, but still most scientists believe that they are of Germanic origin: Rurik, Askold, Dir, Inegeld, Farlaf, Veremud, Rulav, Gudy, Ruald, Aktevu, Truan, Lidul, Fost, Stemid and others. In turn, the names of Prince Igor and his wife Olga are close in sound to the Scandinavian Ingor and Helga. And the first names with Slavic or other roots are found only in the list of the treaty of 944.

The Byzantine Emperor Constantine Porphyrogenitus is one of the most educated people of his time, the author of several works, reports that the Slavs are tributaries of the Ros, and, in addition, gives the names of the Dnieper rapids in two languages: Russian and Slavic. The Russian names of the five rapids are of Scandinavian origin, at least according to Normanists.

The Russians are called Swedes. The Bertin Annals are a chronicle of the Saint-Bertin Monastery in northern France, dating back to the 9th century.

The testimony of Ibn Fadlan, one of the few Arabs who visited Eastern Europe. In 921–922 he was secretary of the embassy of the Abbasid caliph al-Muqtadir to Volga Bulgaria. In his report “Risale”, formatted as travel notes, Ibn Fadlan described in detail the burial ritual of a noble Rus, very similar to the Scandinavian one. The deceased was burned in a funeral boat, and then a mound was erected. Similar burials were actually discovered near Ladoga and in Gnezdovo. Funeral customs are by far the least susceptible to change. In any culture they are taken much more seriously than others, since we are talking about rituals that ensure the well-being of the deceased in the next world, and in the case of any experiments there is no way to check whether he is happy there.

It must be said that the overwhelming majority of Arab sources testify that the Slavs and the Rus are different peoples.

It would seem that everything is clear: the Rus-Rus-Ros are not Slavs, but Scandinavians. But with the help of medieval sources the opposite can be proven. So, for example, in the same “Tale of Bygone Years” there is a fragment that contradicts what we cited above: “... from the same Slavs are we, Rus'... But the Slavic people and the Russians are one, after all, they were called Russia from the Varangians, and before there were Slavs; although they were called polyans, the speech was Slavic.”

Another monument of the 9th century, “The Life of Cyril,” written in Pannonia (Danube), tells how Cyril acquired the “Gospel” and “Psalter” in Korsun, written in “Russian characters,” which a Rusyn helped him understand. By “Russian letters” here we mean one of the Slavic alphabet - the Glagolitic alphabet.

As we see, medieval sources do not give a clear answer to the question of what is the ethnicity of the people who were called to reign in 862. But even if so, why has this problem been bothering people’s minds for more than two hundred years? The point here is not only that scientists are eager to know the truth: the Norman theory has ideological significance. It was formulated in the 18th century by a German historian at the Russian Academy of Sciences - Z. Bayer and his followers - G. Miller and A. L. Schletser. Of course, the Russians immediately saw in it a hint of the backwardness of the Slavs and their inability to form a state. spoke out against the German “insinuation”

M.V. Lomonosov: he believed that Rurik was from the Polabian Slavs. There was another scientist who tried to reconcile the Russian and German points of view - V.N. Tatishchev. Based on the Joachim Chronicle, he argued that the Varangian Rurik was descended from a Norman prince ruling in Finland and the daughter of the Slavic elder Gostomysl. However, later the Norman theory was accepted by the author of “History of the Russian State” N.M. Karamzin, and after him by other Russian historians of the 19th century. “The word Vaere, Vara is an ancient Gothic word,” wrote Karamzin, “and means union: crowds of Scandinavian knights, going to Russia and Greece to seek their fortune, could call themselves Varangians in the sense of allies or comrades.” But Karamzin was contradicted by the writer and scientist S. A. Gedeonov. He believed that the Rus were Baltic Slavs, and the name “Varangians” came from the word warang (sword, swordsman, protector), which the researcher found in the Baltic-Slavic dictionary of the Drevan dialect.

The famous historian D.I. Ilovaisky was also an opponent of the Norman theory. He considered the chronicle story about the calling of the Varangians to be legendary, and the names of the princes and warriors, as well as the names of the Dnieper rapids, were more Slavic than Scandinavian. Ilovaisky assumed that the Rus tribe was of southern origin and identified the Rus with the Roksolans, whom he mistakenly considered Slavs ( modern science speaks of the Sarmatian origin of Roksolan).

In the Soviet Union, the Norman theory was viewed with suspicion. The main argument against it was Engels’ conviction that “the state cannot be imposed from the outside.” Therefore, Soviet historians had to prove with all their might that the “Rus” tribe was Slavic. Here is an excerpt from a public lecture by Doctor of Historical Sciences Mavrodin, which he read during the time of Stalin: “... a thousand-year-old legend about the “calling of the Varangians” Rurik, Sineus and Truvor “from across the sea,” which long ago should have been archived along with the legend about Adam, Eve and the serpent-tempter, the Flood, Noah and his sons, is being revived by foreign bourgeois historians in order to serve as a weapon in the struggle of reactionary circles with our worldview, our ideology...”

However, not all Soviet scientists - anti-Normanists - did not believe in what they wrote about. At this time, several rather interesting hypotheses appeared, the authors of which cannot be called opportunists, careerists, or simply cowards. So, for example, Academician B. A. Rybakov identified the Rus and the Slavs, placing the first ancient Slavic state that preceded Kievan Rus in the forest-steppe of the Middle Dnieper region.

In the 1960s, scientists who were Normanists at heart invented a trick: they believed that the summoned princes were Scandinavians, but at the same time recognized that even before Rurik there had been a certain Slavic proto-state led by Russia. The subject of discussion was the location of this proto-state, which received the code name “Russian Kaganate”. Thus, the orientalist A.P. Novoseltsev believed that it was located in the north, and archaeologists M.I. Artamonov and V.V. Sedov placed the Kaganate in the south, in the area from the Middle Dnieper to the Don. Normanism became popular again in the 1980s, but it should be noted that many scientists adhered to it precisely for reasons of fashion, and scientific dissidence was in fashion at that time.

In our time, the question of the Normans in Rus' remains open. The bans have been lifted, and scientists argue with all their hearts, but we should not forget that the Norman theory was and remains a tasty morsel for scientific ideologists. As an example of an interesting version expressed not by an “ideological”, but by a truly competent researcher, one can cite the theory of a professor at the Department of History of Russia at the Moscow Pedagogical University state university A.G. Kuzmina: “The “Rus” are Slavicized, but originally non-Slavic tribes, and of different origins. At the same time, ethnically different “Russ” participated in education Old Russian state as the dominant layer.

It is known that in ancient sources the very name of the people with the name “Rus” was different - Rugs, Rogs, Rutens, Ruys, Ruyans, Rans, Rens, Rus, Rus, Dews, Rosomons, Roxolans. It turned out that the meaning of the word “Rus” is ambiguous. In one case, this word is translated as “red”, “red” (from Celtic languages). In another case - as “light” (from Iranian languages).

At the same time, the word “Rus” is very ancient and existed among various Indo-European peoples, usually denoting the dominant tribe or clan. In the early Middle Ages, three unrelated peoples survived, bearing the name “Rus”. Medieval Arab authors know them as “three types of Rus”. The first are the Rugians, who originated from the northern Illyrians. The second are the Ruthenians, possibly a Celtic tribe. The third are the “Rus-Turks”, the Sarmatian-Alans of the Russian Kaganate in the steppes of the Don region.”

What can we say in the end? Who were the mysterious Varangians-Rus, about whom “The Tale of Bygone Years” tells? Nobody really knows. The Norman theory these days is more like a religion: you can believe that the Russian state was founded by the Scandinavians, or you can not believe it.

From the book The Bermuda Triangle and other mysteries of the seas and oceans author Konev VictorVikings The Vikings created two main types of ships - merchant and military, which were essentially the same type: merchant and military. The shape of the warship was adapted to sail in rough waters. Such ships have low sides and a wide deck, turning into sharp, gracefully

From the book Who's Who in World History author Sitnikov Vitaly Pavlovich From the book The Great Russian Revolution, 1905-1922 author Lyskov Dmitry Yurievich6. Balance of power: who are the “whites”, who are the “reds”? The most persistent stereotype regarding Civil War in Russia there is a confrontation between “whites” and “reds” - troops, leaders, ideas, political platforms. Above we examined the problems of establishing

From the book Pre-Columbian voyages to America author Gulyaev Valery IvanovichWho are the Vikings? In the old Anglo-Saxon chronicles of the 7th–9th centuries there are many reports of raids by previously unknown sea robbers on the coast of England. Many coastal areas of Scotland, Ireland, Wales, France and Germany were destroyed and devastated.

From book Geographical discoveries author Zgurskaya Maria Pavlovna From the book History of the British Isles by Black JeremyVikings Many European countries in the 8th, 9th and 10th centuries. a second wave of “barbarian” invasions swept through: Hungarians from the east, Arabs from the south and Vikings (Danes, Norwegians and Swedes) from Scandinavia. Vikings - traders, settlers and warriors - moved east to Russia and west to Iceland,

From the book History of Combat Fencing: Development of Close Combat Tactics from Antiquity to the Beginning of the 19th Century author18. VIKINGS There is hardly a person who has not heard anything about the Vikings (Normans, Danes, Varangians). Their constant raids terrified all of Northern Europe and the Mediterranean for two centuries (VIII-IX centuries). But while Charlemagne was alive, the Normans did not attack

From the book The Viking Age in Northern Europe author Lebedev Gleb Sergeevich3. Vikings The social structure of the Hundars and Fylks of the Vendel period did not leave room for the emergence and consolidation of new social forces: elements that came into conflict with the tribal nobility, which relied on sacralized authority, seemed to be “squeezed out” from

From the book History of Combat Fencing author Taratorin Valentin Vadimovich18. VIKINGS There is hardly a person who has not heard anything about the Vikings (Normans, Danes, Varangians). Their constant raids terrified all of Northern Europe and the Mediterranean for two centuries (VIII-IX centuries). But while Charlemagne was alive, the Normans did not attack

From the book Medieval Iceland by Boyer RegisVikings Icelanders took a direct part in the Viking campaigns - the discovery and colonization of the island fits perfectly into the third phase of this process. First-class traders, Vikings, at the first opportunity and where an opportunity presented itself, willingly

From the book History of Humanity. West author Zgurskaya Maria PavlovnaWho are the Vikings? Nowadays, we call Vikings the medieval seafarers who were natives of the lands where modern Norway, Denmark and Sweden are located. The origin of the word “Viking” is a mystery to scientists. The earliest version associates it with the region of Viken in

From the book Archeology of Weapons. From the Bronze Age to the Renaissance by Oakeshott EwartChapter 9 Vikings in Battle Norwegian literature is filled with poetic references to different kinds weapons that were considered fantasies clean water until archaeologists were able to provide specific examples of such weapons that served as evidence

From the book England. History of the country author Daniel ChristopherVikings Vikings were people from Scandinavia who, due to political instability and lack of land, were forced to leave their native lands and seek their fortune in foreign lands. First of all, Europe suffered from them, but the Vikings also reached Constantinople,

From the book Vikings. Sailors, pirates and warriors by Hez YenVikings in the Battle of Hafrs Fjord. Around 872. The only written evidence of this battle is provided only by Icelandic literature, and the authors of the closest sources were separated from the events by at least 200 years (which is why it seems unlikely

From book Medieval Europe. 400-1500 years author Koenigsberger HelmutVikings The origin of the word “Viking” still does not have a satisfactory explanation. This was usually the name given to the Scandinavians, the inhabitants of the Scandinavian Peninsula who were engaged in farming and fishing. Their life was difficult and harsh; they didn't know stone

From the book The Road Home author Zhikarentsev Vladimir VasilievichVikings

The Scandinavian peoples made their presence known on the European stage between 800 and 1050 of our century. Their unexpected military raids sowed fear in prosperous countries that, in general, were accustomed to wars. Contacts between the Nordic countries and the rest of Europe go back a long way, as archaeological excavations prove. Trade and cultural exchange began many millennia BC. However, Scandinavia remained a remote corner of Europe with little political or economic importance.

Arne Emil ChristensenJust before 800 AD the picture changed. In 793, foreigners arriving from the sea sacked the monastery of Lindisfarne on the east coast of England. At the same time, the first reports of raids in other parts of Europe arrived. In the historical annals of the next 200 years we will find many frightening descriptions. Large and small groups of robbers on ships appear along the entire coast of Europe. They move up the rivers of France and Spain, conquer almost all of Ireland and most of England, and set up their settlements along Russian rivers and off the coast of the Baltic Sea. There are reports of predatory raids in the Mediterranean Sea, as well as far to the east, near the Caspian Sea. The northerners who settled in Kyiv were so reckless that they even tried to attack the capital of the Roman Empire, Constantinople.

Gradually, the raids were replaced by colonization. The names of the settlements prove the presence of a large proportion of Viking descendants in the population of Northern England, centered on York. In the south of England we will find an area called Danelagen, which can be translated as “the place where Danish laws apply.” The French king transferred Normandy to fief ownership of one of the Viking leaders in order to protect the country from attacks by others. A mixed Celtic-Scandinavian population developed on the islands north of Scotland. A similar situation was observed in Iceland and Greenland.

The unsuccessful attempt to gain a foothold in North America was the last in a series of campaigns to the west. Around 1000 AD, there is information that the Vikings of Iceland or Greenland discovered a new land far to the west. The sagas tell of numerous campaigns to settle in that land. The colonialists met resistance from either the Indians or the Eskimos and abandoned these attempts.

Depending on the interpretation of the saga texts, the area of the supposed Viking landing in America could stretch from Labrador to Manhattan. Researchers Anne-Stine and Helge Ingstad found traces of an ancient settlement in the north of the island of Newfoundland. Excavations have shown that the structures were similar to those found in Iceland and Greenland. Viking household items dating back to around the year 1000 were also found. It is difficult to say whether these finds are traces of the campaigns that the sagas tell about, or other events about which history is silent. One thing is clear. The Scandinavians visited the North American continent around the year 1000, as is narrated in the sagas.

Population growth and lack of resources

What caused this unprecedented expansion in just a few generations? Stable state formations in France and England clearly could not resist the raids. The picture of that era that we draw on the basis of written sources confirms what has been said, because Vikings are described as terrible robbers and bandits. Clearly they were. But they probably also had other properties. Their leaders were most likely talented organizers. Effective military tactics ensured the Vikings' victory on the battlefield, but they were also able to create stable state structures in the conquered areas. Some of these entities did not last long (such as the kingdoms of Dublin and York), others, such as Iceland, are still viable. The Viking Kingdom in Kyiv was the basis of Russian statehood, and traces of the organizational talent of the Viking leaders can still be seen to this day on the Isle of Man and Normandy. In Denmark, the ruins of a fortress from the end of the Viking Age, designed for a large number of troops, have been found. The fortress looks like a ring, divided into four sectors, each of which housed residential buildings. The layout of the fortress is so precise that this confirms the leaders' penchant for systematics and order, as well as the fact that among the Vikings there were experts in geometry and surveyors.

In addition to Western European information sources, Vikings are mentioned in written documents from the Arab world and Byzantium. In the homeland of the Vikings we find short writings on stone and wood. The 12th century sagas tell a lot about Viking times, despite the fact that they were written several generations after the events they narrate.

The homeland of the Vikings was the territories that now belong to Denmark, Sweden and Norway. The society from which they came was a peasant society, where agriculture and animal husbandry were supplemented by hunting, fishing and the manufacture of primitive utensils from metal and stone. Although the peasants could provide themselves with almost everything they needed, they were forced to buy some products like, for example, salt, which was needed by both people and livestock. Salt, an everyday product, was purchased from neighbors, and “delicacies” and specialty goods were supplied from the south of Europe.