Send your good work in the knowledge base is simple. Use the form below

Students, graduate students, young scientists who use the knowledge base in their studies and work will be very grateful to you.

ABSTRACT

Subject: Theoretical basis household economics

1. Household choices and their limitations

2. Household preferences

3. Optimal household consumption plan

4.Main factors influencing household demand

5. Household supply

Bibliography

1. Household choices and their limitations

The household, as one of the subjects of microeconomics, plays an extremely important role in the system of economic relations.

Firstly, satisfying the household's needs for material and intangible goods is the natural goal of production. Household demand is one of the most significant components of aggregate demand for final goods. Secondly, households, as owners of production factors, transfer them to business units (enterprises), which must effectively combine them. Thirdly, the part of the income that is not used by the household during the current period is converted into savings and can, under certain circumstances, become a powerful source of economic growth for the country. It can be stated that a household performs three main functions in the economy: consumption, supply of production factors and savings. Thus, a household is an economic unit consisting of one or more people, leading general farming, which provides the economy with factors of production and uses the funds earned from this for the current consumption of goods and services in order to satisfy its needs. At the same time, from the point of view of the microeconomic level of management, the leading function for a household is, of course, the consumption function.

In order to analyze how a household performs this function, economics resorts to a number of abstractions that allow us to study the behavior of the object of analysis in pure form. First, the household is considered to be a single economic entity and realizes its needs as a whole, i.e. its internal structure is not taken into account; it is identified with the concept of “individual”. Secondly, it is assumed that a household receives income through the sale of factors of production, more precisely services, or use and redistribution among their members of society and spends its income entirely on consumption without making savings. Thirdly, it is believed that it can consume all consumer goods that are produced by this moment production sector, and these benefits are considered infinitely divisible in the presence of complete information about the consumer properties of goods. Fourthly, household actions that may affect current consumption are not taken into account, namely: increasing or decreasing property, obtaining a loan, or investing part of the income in consumer goods.

Under such circumstances, the household is faced with a choice: it needs to distribute cash income among various goods that satisfy its needs. It is this process that primarily interests economists, i.e. how a household makes decisions on a certain consumption pattern.

A household’s choices are limited by many factors: the level and structure of production, the structure of the needs of this household and the level of saturation of some of them (thus, they are quickly saturated when normal conditions needs for basic food products, while spiritual and social needs practically do not know the limits of saturation; as physical needs are satisfied, consumption switches to needs more high level), household income level, since in conditions market economy the overwhelming majority of economic goods are provided only in exchange for money, a price level established by the market, which the household, due to the fact that it is only one of a huge number of consumers of goods, cannot decisively influence, and therefore accepts it as it is. The totality of sets of goods available to a household under such restrictions is the space in which the household has freedom of action in relation to consumer choice. Thus, the household must solve the problem: given a certain structure and level of needs and income, find a combination of consumer goods that would best suit its needs.

If the needs of the household are a variable value, then the level of income is a cash value that financial side sets the boundary for satisfying needs, in other words, together with prices, it represents budget constraint. Since, in accordance with the previous assumptions, all household income must be spent on consumption, the budget constraint takes the form:

Where M- income received for a certain period; p i - R P - prices of consumer goods; x i- X P - the volume of consumption of a certain good.

So, if the income received is 100 den. units, and food prices X 1 And X 2 are 5 and 10 den, respectively. units, the budget constraint will be 100 = 5x 1 + 10x 2.

A set of consumption plans that satisfies this constraint is called financially feasible consumption plans. As can be seen from Fig. 1, the set of financially possible plans is limited by a straight line corresponding to the budget constraint. Consumption plans A And IN are financially feasible, whereas S is not. However, since the household, in accordance with the assumptions, must spend all its cash on consumption, it will implement only those plans that lie on the budget line M. The intersection points of the budget line graph with the coordinate axes show how much of one good an individual can consume if he completely refuses from consuming another.

Rice. 1 - Budget constraint and set of financially possible consumption plans for a household

The financial capabilities of a household are influenced by the amount of income M received (the larger, the wider these opportunities under other constant circumstances), prices for goods and all factors that determine changes in these parameters, for example, income taxation, the introduction or increase of taxes on consumption, rationing, etc. P.

2. Household preferences

Based on the available budget, the household must make its choice from numerous financially possible plans. What is it guided by? Ideas about the extent to which a certain good can satisfy his needs. Thus, an individual must give preference to one of the available consumption options to the exclusion of all others.

Let us analyze the choice of a household (individual) in some conditional extreme situation. Let's imagine that someone N, While attending a theatrical performance, during the intermission I went to the buffet to satisfy my hunger a little. However, unfortunately, he arrived too late, and there were only two sandwiches left in the buffet - one with cheese, the other with sausage. All existing consumption options N limited in quantity and characterized by varying levels of desirability and usefulness. First of all N would like to eat both sandwiches; if there is only enough money for one, then any of them, but if there is not enough money even for one sandwich, then leave without eating anything. This characterizes the order of preferences of an individual. Which alternative will be implemented depends only on the budget N.

This hypothetical example shows that the order of a household's preferences must correspond to certain properties that together describe rational consumer behavior.

Firstly, N, as we have seen, chooses one of the available alternatives, determining which one is better. This means that an individual must be able to evaluate sets of goods in terms of their compliance with his needs and budgetary capabilities. This preference property is called completeness.

Secondly, N doesn't need to match everything possible options consumption with each other; It is enough for him to know which of them is best for him, i.e. he probably knows that eating one sandwich is better than nothing, but even better is eating both, and with such a choice there is no longer any need to compare the option with an empty stomach. This preference property is called transitivity.

Thirdly, knowing his preferences, N implements the financially feasible plan that has the highest rating for him, i.e. first. This preference property is called rational choice after all, the individual must realize the best consumption plan available to him.

Completeness and transitivity of preferences, rationality of choice are the main properties of the order of household preferences, although the list is not exhaustive.

Performed preference analysis N showed that he evaluates two of the available consumption plans equally, i.e. indifferent. If you connect points on a graph that reflect all consumption plans to which an individual is indifferent (indifferent), you can get a curve U, called curve of indifference (indifference), which is shown in Fig. 2. Obviously, such curves that are graphic image there can be an infinite number of consumption plans, so they say that the individual has "card of indifference." Since higher indifference curves should accommodate consumption plans that are given preference over those on lower curves, the consumer's goal is to achieve the highest achievable indifference curve, or, in other words, to most fully satisfy one’s needs, to maximize one’s utility ( beneficial effect from the consumption of a certain set of goods).

Rice. 2 - Household indifference curve

The presence of consumption plans, between which the individual is indifferent, means that the individual, satisfying his need, can, in a certain proportion, replace the consumption of one good with another. So, when moving from consumption plans A(includes 3 units of benefit X 2 and 1 unit. benefits x 1) to IN(respectively, 2 units of good x 2 and 4 units of good x 1) the consumption of good x 2 is replaced by good x 1. However, it is clear that with a further decrease in consumption of the good X 2 the individual will be less and less willing to act this way, since in order to remain on the same indifference curve (utility level), he needs to receive in return more and more units of good x 1. Thus, his tendency to replace good x 2 with good x 1 decreases . The indicator characterizing this propensity is called maximum replacement rate(PNZ). Quantitatively, it represents the ratio of changes in consumption of a good X 2 to a change in consumption of the good x 1, where the minus sign indicates negative character dependencies between variables:

From the considered properties of indifference curves, it is clear that the cost of production must constantly decrease.

The justification for the diminishing property of PPP involves an analysis of the factors that determine the value of a good for an individual, which depends on its relative rarity and rarity. When switching from plan A to plan IN quantity of goods X 2 the individual will decrease. It becomes more rare, while for the good X 1 it's the other way around. Thus, the substitution of units of the good X 2 as its quantity decreases by increasingly larger volumes of good x 1 is associated with a change in the ratio of the rarity of these goods for the individual.

Understanding the properties of an individual's preferences leads to an understanding of how one can measure the utility of a particular set of goods that an individual can choose. IN economic theory In this regard, there are two concepts: quantitative and ordinal.

Essence quantitative concept of utility, the theoretical foundations of which were laid by representatives of the Austrian economic school at the end of the 19th century. (K. Menger, F. Wieser, E. Böhm-Bawerk, etc.), is that an individual is able to measure the amount of “utility” that he has from the consumption of each good, and therefore from a certain set of goods. A modern quantitative approach to household utility is presented in the textbook Economics: Principles, Problems and Policies by K. R. McConnell and S. L. Brew. According to this concept, consumer behavior is reduced to choosing a more useful plan. However, one fundamental question remains unclear: how to measure utility, in what units?

Essence ordinal concept of utility, The ancestors of which are considered to be the Italian economist and sociologist V. Pareto and the Englishman F. Edgeworth, is that the plan that an individual chooses under certain restrictions is the best, meaning for him the highest utility. It is the order of preferences that makes it possible to determine the degree of desirability of this set of goods for an individual, and therefore there is no need to resort to a quantitative definition of utility. The ordinal concept of utility is the theoretical foundation modern theories demand.

3. Optimal household consumption plan

When choosing a consumption plan, a household strives to implement the financially possible plan that it prefers over others, since it means the highest utility for it. The consumption plan that, given a budget constraint, gives an individual maximum utility is called optimal consumption plan.

Determining the optimal consumption plan comes down to a comparison of the individual's desires, represented by his preferences, and the possibilities provided by the budget constraint.

Faced with the need to choose, the individual chooses the best available plan A x 1 ,X 2 ), since the plan IN although it meets the conditions of the budget constraint, it is located on an indifference curve, which is not the highest achievable level of utility (Fig. 3). Thus, achieving more complete satisfaction of needs, which is the economic content of utility maximization, the individual will move along the budget constraint M up to the point A, which gives the consumption plan with the highest (given restrictions) utility. For the consumption plan that is being implemented, it is characteristic that the angle of inclination of the budget line (and it corresponds to the ratio of prices for the good X 1 And X 2 ) equals the slope of the indifference curve at this point, which corresponds to the value of the PNI, i.e. there is a relation:

Plan C, of course, is even better, but, unfortunately, unattainable with this volume of financial resources and prices for goods.

Rice. 3 - Optimal household consumption plan

Thus, it is possible to formulate sufficient and the necessary conditions implementation by an individual of an optimal consumption plan:

1) income must be spent on consumption without leaving a trace;

2) the marginal rate of substitution must be equal to the price ratio.

The conditions for achieving the household's optimal consumption determined in this way are key to understanding the factors of individual demand for a particular good.

4. Main factors influencing household demand

Household demand is influenced by a combination of factors, among which the most significant are preferences, income, prices, and the volume of household property.

A change in income leads to a change in the budget constraint: if income increases, then there is a parallel upward shift in the budget line; if it decreases, down. In accordance with this, the individual will move to consumption plans that are different from the original ones. The curves transferred to a separate graph, reflecting the dependence of the demand for a particular good on the amount of income, are named after the scientist who first did this, Engel curves. There are three possible types of consumer reaction to a change in income: a) a change in the volume of consumption of a good in the same direction; b) a change in the volume of consumption of a good in the opposite direction; c) lack of demand response to changes in income. In accordance with the first two types of reaction, households distinguish between higher and lower goods.

Under the highest blessings understand those for which the volume of demand increases with an increase in income, and decreases with a decrease. A typical example would be goods that satisfy spiritual needs.

Under inferior understand goods, the volume of demand for which decreases with an increase in income, and increases with a decrease. These are, for example, goods that satisfy physical (especially physiological) needs, such as the need for certain types food products.

The degree of demand response to changes in income is measured by the indicator income elasticity, which shows the degree of change in quantity demanded depending on changes in income.

However, this classification of consumer goods cannot be made absolute, bearing in mind the household’s mode of action. It is relative in nature: with a low level of household well-being, “typical” lower goods will be the same as higher ones; when the level of saturation of the need for a “typical” higher good is reached, it will begin to reveal features of the lower, etc. In other words, everything depends on the initial income base and the level of satisfaction of needs.

Another demand factor that receives primary attention in microeconomics is prices. Moreover, it is necessary to distinguish between the influence on demand of both the direct price of this good and the prices of other goods that are in a certain connection with it.

The reaction of household demand to a change in the price of a certain good is due to the shift in the budget line caused by this, which will result in its rotation, a change in the angle of inclination according to the direction in which the price changes (Fig. 4). As a result, the individual will implement a different consumption plan in accordance with the new budget constraint.

Rice. 4 - Obtaining the household demand function

Increasing the price of a good X 2 led to a downward turn of the budget line and the transition of the individual to a lower indifference curve and, accordingly, to the choice of new optimal plans. Putting aside the value of the price of the good x 2 and the corresponding volumes of demand for it on a separate graph, we get demand curveX 2 " (left side in Fig. 4). It is a graphical representation of the household demand function and shows how much the individual’s demand for a good will change depending on a certain price level for it. In this case, due to an increase in price, the quantity demanded decreases. This relationship between price and demand is typical for ordinary benefits. If, as the price increases, the quantity demanded increases, this good is called Giffenian (named after the English economist R. Giffen, who first recorded such a reaction by analyzing the demand for bread from the poorest segments of the population). The anomalous nature of the response of demand to price changes is explained by the fact that at a low level of income, when households spend it almost entirely on satisfying the first living needs, an increase in prices for these rather cheap, compared to other, goods will lead to households refusing consumption of more expensive quality products and will consume cheap goods despite rising prices for them.

At the same time, the phenomenon of an increase in demand when prices increase (Giffen's paradox) is possible in other cases not related to the situation low level household income. For example, when consumers evaluate the quality of consumer goods not on the basis of studying their use value, but in accordance with the price level, believing that a higher price is an indicator of higher consumer qualities (although life often shows that in many cases this is not the case); when consumers buy certain goods to support their own prestige (the so-called snobbery effect); Finally, such a reaction is possible in the case of high inflation expectations of the population, when goods are purchased at an increased price today only because tomorrow they will cost much more.

The degree of reaction of household demand for a certain good in accordance with changes in its price is characterized by the indicator price elasticity. It shows how much demand will change if the price level changes by one percent:

Accordingly, if e< 0 , мы имеем дело с обычным благом; приe> O - with Giffensky. If the elasticity is zero, then the demand for this good is inelastic, i.e. does not react in any way to price changes. The greater the absolute value of the elasticity indicator, the more sensitive the household demand will respond to price changes.

Household demand also responds to changes in the prices of other goods. Thus, if a certain good is consumed in combination with another (for example, a car and fuel, coffee and sugar), which complements its consumer qualities, a change in the price of this complementary good will cause opposite changes in the demand for this good: an increase in price for coffee at a constant price of sugar will cause a decrease in the demand for coffee, and therefore for sugar as a complementary good to it. If there are substitutes for a good, an increase in its price while the prices of substitutes remain constant will cause a switch in demand for these goods. Continuing the above example, tea can be called a substitute for coffee: an increase in the price of coffee will lead to an increase in demand for tea.

The degree of response of demand for a certain good depending on changes in the prices of other goods is measured using the indicator cross elasticity. It shows how much the demand for that good will change if the price of another good changes by 1 percent:

If? x 1, p 1 >0, then the good x 1 is in a substitute relationship with the good x t; if? x 1, p 1<0, то в комплементарной.

The nature of the influence of various factors on household demand for a particular good is summarized in Table. 1.

Table 1 - Classification of goods in accordance with demand response

Analyzing the impact of price variations on household demand, economists (J. Hicks, E. Slutsky, etc.) came to the conclusion that the overall effect of price changes can be decomposed into two effects: a) the income effect, since an increase in the price of a good means a decrease in real income households, and vice versa; b) the substitution effect, since a change in price causes certain changes in the demand for other goods that are in a complementary or substitute relationship with it. Taking these effects into account is very important when analyzing the consequences of price shifts, in particular when implementing direct or indirect government intervention in the price mechanism: these measures can differently influence the demand of individual groups of the population depending on their level of income, structure of needs, etc., and therefore, cause socio-economic consequences that are exactly the opposite of those expected.

5. Household supply

When studying a household as a consumer, it is assumed that the household has a certain income with which it satisfies its needs. In turn, the amount of income received depends on the price and volume at which the household sells its production factors. The most significant factor of production that a household has is work. By selling their working time at prevailing wage rates (hourly, weekly, monthly, annual), individuals receive a permanent source of income, which finances current consumption. However, by spending his time on generating income, the individual gives up the alternative opportunity - not to work, i.e. from free time, which is one of the important goods consumed by an individual. Lack of free time leads to defective personality reproduction and premature aging of the body. In other words, the individual faces a choice: work more and, accordingly, consume more market goods or relax more. The main factors that he takes into account are the time fund (taking into account the need to satisfy physiological needs), the wage rate and the price level for consumer goods. Thus, the level of utility is determined by the volume of consumption and free time.

The budget constraint in this case will look like:

Where w - wage rate; T- general fund of time; F - free time; R- the price of a consumer good; X- the volume of consumption of a good (the aggregate of all goods except free time).

Solving the equation with respect to X transforms the budget constraint into the following expression:

If an individual has ordinary preferences regarding X And F finding the optimal consumption plan occurs similarly to the approach outlined in part 3 of this abstract, i.e. marginal rate of substitution between free time and consumption of a good X must be equal to the ratio of the wage rate and the price of the good X(Fig. 5).

Rice. 5 - Optimal household plan taking into account free time

Knowing the optimal free time, you can calculate the optimal amount of working time. For this, from the general fund of time T free time is deducted, i.e.

T- F = L,

Where L - optimal working hours.

The situation may change if the household receives income independent of labor (profit, rent, interest, social assistance, etc.). This will lead to a parallel upward shift of the budget line and a change in the optimal plan. Depending on the order of the individual's preferences, this may result in either a reduction in free time and an increase in working time, or, more likely, an increase in free time. In the extreme case, an increase in income independent of the labor factor can lead to the fact that in the optimal household plan the value of free time will be equal to the total fund of time. Thus, the individual will not work at all.

By varying the wage rate, one can study the relationship between its value and labor supply, i.e. the amount of time that an individual is willing to sacrifice in favor of consumption. Theoretical modeling and empirical studies have shown that the labor supply of a household depends ambiguously on the wage rate: at certain values w it increases, while in others it decreases (Fig. 6).

Rice. 6 - Individual labor supply curve

So, if w 1 < w 2 the individual will increase working hours, since with a decreasing wage rate, compensation for the decrease in income is possible only through an increase in the volume of work. For example, the insufficiency of wages received at the main workplace to meet basic living needs forces able-bodied family members to look for additional work in their free time. If w t < w 1 < w 2 An increase in wages stimulates the desire to earn money, i.e. sacrifice free time for the benefit of the worker. At the same time, an increase in the wage rate can only be accompanied by an increase in labor supply to a certain extent: at a certain critical value w = w 2 an increase in wages will lead to the opposite results - the supply of labor will begin to decline, since with high incomes the individual begins to value free time more and more. In addition, there is no need to work more, since wages satisfy the needs of the household.

Bibliography

1. Belyaev O.O. Economic policy: Head. pos_b. - K.: KNEU, 2006. - 288 p.

2. Bazilevich V.D. Polytheconomy. - K.: Znannya-Press, 2007. - 719 p.

3. Stepura O.S. Political economy: Navch. pos_b. K.: Condor, 2006.

4. Economic theory: Pidruchnik / edited by V.N. Tarasevich. - K.: Center for Basic Literature, 2006.

5. Bashnyanin G.L., Lazur P.Yu., Medvedev V.S. Political economy. - K.: Nika-Center: Elga, 2002.

6. Polytheconomy. Navchalny handbook / Ed. Nikolenko Yu.V. - K.: Znannya, 2003.

Similar documents

Households as market subjects. Concepts, main features, functions and types of household. Income and expenses of a modern household. Rational consumer behavior in a market economy. Social and insurance payments to households.

course work, added 05/19/2014

The essence and internal structure of households, their classification and varieties, characteristics and properties as subjects of a market economy. Analysis of household income and expenses, modern problems in Russia, trends and development prospects.

presentation, added 12/04/2013

The role and place of household finance in society. Providing investment in the economy through direct and indirect (through the financial market) investment of savings. Household budget structure and planning. Creation of non-corporate market enterprises.

course work, added 05/30/2014

Household in the system of regional differences in consumer relations. The essence and functions of the home economy, methods of measuring household work. A transactional approach to the study of family and home economics. Problems of farms in Russia.

course work, added 04/04/2016

The problem of the adequacy of reform projects to Russian realities. Households: non-market adaptation to the market. Economics of individuals, paternalism and barter. The formation of private property. Conditions for the transition of the economy to an innovative path of development.

abstract, added 09/30/2009

Introduction to the concept of household; its role and functions in the circulation of resources, money, goods. Interaction of the main institutions of a market economy. State monetary policy for the development of households, development problems.

course work, added 05/29/2013

The concept of standard of living and its components. Development of a generalizing (integral) indicator of the standard of living of the population. Concept of family and household. Dynamics of the cost of living in Russia. Indicators of accumulated property and housing provision for the population.

course work, added 06/09/2014

Statistical methods for studying the level and quality of life of the population using the example of “Households of the region’s population.” Analysis of gross food income per household member per year. Identification of patterns of changes in the well-being of the population.

course work, added 03/19/2011

Market of goods. Factors of consumer demand. Absolute income hypothesis. Modern modification of the Keynesian consumption function. Intertemporal budget constraint, investment demand. Demand from the state and abroad. Pure export function.

presentation, added 12/17/2013

The essence of consumption and savings. Aggregate demand. Contents of savings. Features of consumption and savings in Russia. Trends in savings behavior of the population. Dependence of consumption and savings on the level of economic development.

Object The characteristics of the category of consumption and savings are a closed private economy. This means that government expenditures and net export expenditures are not included in the overall expenditure profile. Under these conditions, GDP is defined as the sum of C + and. Where C is household expenses for the purchase of goods and services, and is the amount of investment costs.

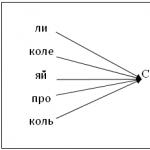

1. Considering the first question, we draw attention to the fact that one of the links in modern macroeconomic models is the goods market. The structural and logical diagram of teaching the first question has a general form (Fig. 1).

Any national market consists of certain individual markets. Conventionally, we can say that it includes the market for goods and services, the market for scientific and technical products, the labor market, the financial market, and the like. Each of the listed markets has its own system of organization.

Rice. 1.

In macroeconomics, the entire set of markets for individual goods, which are the subject of macroeconomic analysis, is aggregated into a single market for goods, in which only one type of goods is bought and sold. This good can be used both as a commodity and as a means of production.

The market for goods and paid services is a system of economic relations between business entities regarding their movement. This movement leads to the satisfaction of consumer and investment demand of business entities.

Consumer demand - is the effective demand of households for:

Current consumption goods (35-40%);

Durable goods (15-20%);

Services (35-40%).

The structure of consumer spending itself is variable and this change is influenced by many factors.

Investment demand - this is the demand of the business sector for goods to restore worn-out capital and increase real capital.

The basis for the interaction of firms and households in the goods market is the proportion in which income (Y) is distributed between consumption (C) and savings (B).

Buyers in the goods market are the main macroeconomic entities: the household sector, the business sector, government and foreign. Let's look at what determines the volume of demand.

More than half of final aggregate demand comes from household demand. The share of production of consumer goods in developed countries is more than 60%.

Consumption priorities are different, but the most characteristic groups of goods and services for a family can be identified: food, clothing, housing, education, medical care, recreation, transport, etc.

The amount of consumption depends on family income, whether services are paid or free.

Poor families spend their income on essential goods. As income increases, the share of food expenses decreases. Expenses on clothing, durable goods, and vacations are growing faster than income.

For developing countries, food costs account for the majority of income. The population of Ukraine is characterized by a large share of the poor and, as a result, spends almost all of its income on food and the purchase of essential goods. Unfortunately, it is difficult to determine and calculate the current expenses of the population of our country, since the high proportion of the shadow economy does not allow us to trace the flows of goods and money.

Household demand is determined by the following factors:

Income from participation in production;

Taxes and transfer payments;

Size of property, income from property;

The degree of differentiation of the population by income level and size of property;

Number and age structure of the population.

Consumption represents the individual and joint use of consumer goods, which is aimed at satisfying the material and spiritual needs of people. Its amount depends on income.

Saving - economic process associated with investment. This is the part of income that remains unused after funds have been allocated from firms for current production needs, and to households for consumer needs.

The distribution of income (U) for consumption (C) and savings (B) is carried out by economic entities taking into account:

First, preferences between current consumption and future consumption;

Secondly, the current interest rate.

Savings are carried out by both firms and households.

Investment (I) is carried out by firms in order to expand production and increase profits.

Equilibrium in the market for goods and paid services in a closed model of the economy, in which the activities of the state are not taken into account, is achieved when the supply of savings is equal to investment demand.

The supply of savings (B) is a function of income (Y):

The relationship between B and C is direct.

Investment demand (I) is a function of the market interest rate (and):

The relationship between investment demand (I) and interest (i) is inverse (the more and, the less I).

Equilibrium in the market for goods and paid services is expressed by the formula:

Movement in the goods market makes it possible to more fully satisfy the needs for consumption and investment. Thus, general equilibrium with a constant price level in the markets for goods and services is possible if the equilibrium conditions are met in each of the markets.

2. Considering the second question, “Consumption and savings as functions of income,” let us pay attention to the structural and logical diagram of the interaction between consumption and savings:

Optimization of macroeconomic proposals is achieved through the mechanism of supply and demand. Consider the problem of matching supply and demand in accordance with the owners of capital and labor.

Firms, whose administration acts as representatives of capital, produce products, sell them and earn money for it and create demand for labor. Workers offer their labor, receive remuneration for this and create demand for manufactured products. Based on the interaction of firms and households in the market for goods and services, the proportion of GNP distribution between consumption and savings is determined.

Rice. 2.

Consumption (in value form) is the amount of money that is spent by the population on the purchase of material goods and services.

Thus, everything that does not relate to savings, is not included in payments in the form of taxes, is not in foreign accounts - this is consumption.

People tend to delay consumption today with the hope that consumption in the future will benefit them more than it does today.

The primary unit of consumption is the family. It shapes the volume and structure of consumption. A family household is characterized by a general consumer budget, housing and accumulated property.

Population consumption- one of the main components that determine economic development. Consumer spending accounts for between 2/3 and % of gross domestic product. They shape consumer behavior, which is a kind of indexer of the cyclical development of the economy.

To assess consumer behavior, an indicator is used - the Index of Consumer Sentiment (ICH). It is included in the main macroeconomic indicators on the basis of which economic cycle forecasts are made. This is important both for short-term planning of any business and for determining the economic policy of the state.

The consumer sentiment index was developed in 1946 by SPIA. However, its intensive use began in the 70s. The practical use of the index for analyzing the Ukrainian economy began in 1994

Saving- This is deferred consumption or that part of income that is not currently consumed. They are equal to the difference between income and current consumption.

Savings are carried out by both firms and households. Firms save to invest in expanding production and increasing profits. Households save for a number of reasons, including: the motives of providing for old age and passing on inheritance to children, saving funds for the purchase of land, real estate and important durable items.

Savings and investments are carried out independently of each other, by different economic entities and for various reasons.

How are profits allocated between consumption and savings? In answering this question, it is important, first of all, to characterize the general properties of the consumption function. It shows the ratio of consumer spending to income as it moves.

Household personal consumption (C) forms the most important component of effective demand. But if we remember that savings (B) represent the excess of income over consumer spending, it becomes clear that when analyzing the factors that determine consumption, we simultaneously consider the factors on which savings depend:

where B is income;

C - consumption; B - savings.

This equation shows that part of the income goes to personal consumption C, and the excess takes the form of savings B. At the same time, society’s expenses can be represented, on the one hand, as demand for consumer needs C, and on the other, for investment needs I:

In a formalized form, consumption can be expressed by the following function:

However, income is the main factor determining not only consumption, but also savings:

Research has found that consumption moves in the same direction as income. The dependence of consumption and saving on income is called the propensity to consume and save. Consider the average and marginal propensity. Average propensity to consume APC is the share of tax-free income allocated to consumption.

where C is the amount of consumption, Ud is tax-free income.

Similarly, we can look at the average propensity to save (APS). Average Propensity to Save APS is the proportion of tax-free income allocated to savings.

The marginal propensity to consume expresses the ratio of any change in consumption to the change in income that caused it. Mathematically it looks like this:

MPC shows how much of the additional income is allocated to additional consumption. The sum of the marginal propensities to consume and save under any change in tax-free income is equal to 1 or 100%.

The marginal propensity to save is the ratio of any change in saving to the change in income that caused it.

How are these indicators determined? Let's consider a table hypothetically and analyze it.

The first column contains groups of families depending on the level of average per capita annual income. When moving from group B to group C, income increased by 300 gr.od., that is, from 900 to 1200 gr.od. At the same time, consumption increased by only 240 g.o. (from 900 to 1140 deg.). Thus, the share of consumption in the increase in income can be calculated as follows: 240/300 = 0.8, that is, when moving from group B to group C, from each additional monetary unit of income, 80% goes to consumption and 20% to savings, the marginal the propensity to consume in this segment is 0.8.

MPC is calculated similarly when moving from any income level to the next.

Both consumption and savings are growing absolutely, but the relative share of consumption is increasingly decreasing, and the share of savings is growing. So, according to the “basic psychological law,” the value of the marginal propensity to consume is between zero and one:

From here we draw conclusions:

If MPC = 0, then the entire increase in income will be saved, because saving is that part of income that is not consumed;

If MPC = /, then this means that the increase in income will be divided equally between consumption and saving;

If MPC = 1, then the entire increase in income will be spent on consumption.

When moving from group B to group C, income increased by 300 GR, but savings increased by only 80 GR.

The marginal propensity to save will be calculated as the increase in savings to the increase in income: 60/300 = 0.2.

When moving from group B to group C, the marginal propensity to save will be 0.2.

It is easy to see that if C + S = Y (i.e. total income is divided into consumption and savings). Then the sum of the marginal propensity to consume and the marginal propensity to save is equal to 1:

Having defined the function of consumption and saving, we can now argue that the central factor that influences their level is income. As a rule, as income increases, both consumption and savings of the population increase. At the same time, in conditions of stable economic growth, MPC tends to decrease, and MPS tends to increase. In conditions of inflation, another process is observed, namely: MPC tends to increase, and MPS tends to decrease. When the economic situation is unstable and deposits are not protected from inflation, the population begins to increase consumption, especially of durable goods. A unique type of savings in such conditions is the purchase by the population of goods such as jewelry, furs, cars, dachas, etc.

In addition to these factors, consumption and savings can be influenced by:

Increase in taxes, which reduces consumption and savings, increases in prices (causes different reactions to consumption and savings among population groups with different incomes)

An increase in social security contributions (may cause a reduction in savings);

Excessive demand (can contribute to a sharp increase in consumption);

Increased supply in the market (contributes to a reduction in savings);

Income growth (affects the growth of consumption and savings).

Macroeconomic income involves constructing the consumption and savings function at the societal level.

Using the input data from the table, let's turn to a graphical analysis of the propensity to consume.

Graphically, the consumption function is presented in Fig. 2.

How is this graph constructed? The x-axis shows income available for use. On the y-axis - consumption expenditures exactly corresponded to income, then this would be reflected by any point belonging to a straight line drawn at an angle of 45. But in reality such a coincidence does not occur, and only part of the income is spent on consumption. Therefore, the consumption curve deviates downward from the 450 line. The intersection of line 450 and the consumption curve at point B means the level of zero savings. To the left of this point one can observe negative savings (in this case, expenses exceed income), and to the right - positive savings. The amount of consumption is determined by the distance from the abscissa axis of the consumption curve in line 450. For example, with an income of 2400 gr.od. the situation is as follows: segment D1D shows the amount of consumption, and segment DD2 shows the amount of savings.

Fig 2.

The saving function, which is a derivative of the consumption function, is treated similarly. The savings function shows the ratio of savings to income in their movement (Fig. 3). Since savings are that part of income that is not consumed, the savings schedule complements the consumption schedule. This is due to the fact that savings and consumption in total will give the amount of income.

Rice. 3.

How is the savings schedule constructed? To do this, you need to carry out a number of simple operations: first, imagine the x-axis in Fig. 3. like the 45° line from fig. 2; secondly, it is possible on the 45° line from Fig. 2. place a mirror - the graph reflected there will be the image of savings in Fig. 3. Point B is the level of income when saving is zero. Below it is negative savings, above it is positive savings.

The marginal propensity to consume MPC, as noted above, reflects the amount of additional consumption caused by additional income. On a graph, this is expressed by the slope of the consumption curve: a steep slope means high MPC, and a smooth slope means low MPC. MPC is nothing more than an expression of the steepness of the slope of the consumption line. Returning to the consumption graph, we can conclude that the greater the propensity to consume, the more the consumption line will approach the 45 line and, accordingly, vice versa, the lower the propensity to consume, the further the consumption line is from the 45 ° line.

Buyers in the goods market are all four macroeconomic entities: households, the business sector, the state and abroad. Let us consider what determines the volume of demand for the benefits of each of them.

2.1.1. Household demand

The main factors determining household demand in the goods market include:

· income from participation in production;

YD = Y – t * Y + TR,

TR– the amount of transfers.

Therefore, it would be more accurate to represent the consumption function as

C = Ca + cYD * YD; Ca > 0; 0 < cYD < 1, (2.1a)

Where - cYD= ∆C/∆YD marginal propensity to consume disposable income.

Thus, the Keynesian consumption function has the form presented in Figure 2.1 and has three important properties .

Firstly , the main determinant of consumption is income Y.

Secondly , one of its parameters is the marginal propensity to consume c, based on a “basic psychological law” and lying between 0 and 1.

Third , average propensity to consume (ratio of consumption to income C/Y=Ca/Y+c) decreases as income grows and tends to a constant marginal propensity to consume (see Figure 2.2.). From this property, in particular, it follows that in the Keynesian concept, the expansion of production potentially contains the possibility of overproduction (an ever smaller part of the produced products is consumed by households).

C c, C/Y

C c, C/Y

C = Ca + c * Y C / Y

Y Y

Since saving is the unconsumed part of income, then in the Keynesian concept saving function is obtained by subtracting the consumption function from income:

S = Y - C = Y – (Ca + c * Y) = - Ca + (1-c)Y = - Ca + s * Y,

Where s = ∆S/∆Y– marginal propensity to save, complementing the marginal propensity to consume to 1: c +s = 1.

A practical test of function (2.1) in the middle of the 20th century showed that it quite accurately describes the patterns of consumer behavior in a short (2-4 years) period. At the same time, calculations based on actual data carried out over longer periods of time indicate that the average consumption rate has remained unchanged. The first to draw attention to this was the American economist Simon Kuznets, who later received the Nobel Prize for this research. “The Blacksmith's Riddle” has intensified research into consumer behavior. A modern explanation for the “Kuznets riddle,” i.e., the fact that the properties of the consumption function proposed by Keynes are not confirmed by statistical data over long time intervals, was provided by studies by economists who proposed modifying the Keynesian consumption function. The most interesting of them are the hypothesis “ life cycle” F. Modigliani and the concept of permanent income M. Friedman, proposed in the 1950s and focusing on long-term consumption research.

The life cycle concept views individuals as if they plan their consumption and saving behavior over long periods with the intention of distributing their consumption as best as possible over their entire life span. The life cycle hypothesis considers saving as a consequence of individuals' desires to ensure necessary consumption in old age.

The life cycle concept views individuals as if they plan their consumption and saving behavior over long periods with the intention of distributing their consumption as best as possible over their entire life span. The life cycle hypothesis considers saving as a consequence of individuals' desires to ensure necessary consumption in old age.

Consider an individual who expects to live Tj years old, work Tr years, receiving an annual income yt. Suppose that his savings do not earn interest, so that current savings are completely transferred to future consumption opportunities. It is logical to assume that an individual will want to distribute consumption throughout his life in such a way as to have a uniform flow of consumption..gif" width="90" height="92">.

Thus, during the working period, an individual’s consumer expenses are financed from current income, and during the retirement period - from savings. In other words, The essence of life cycle theory is that an individual's consumption plans are drawn up in such a way as to ensure a uniform level of consumption throughout life by saving funds during periods of high income and spending them during periods of low income . It should be noted that the life cycle theory contains more general theory Savings: People save a lot when their income is high relative to their average lifetime income and spend down their savings when their income is low relative to their average lifetime income.

Let us expand this model by assuming that an individual has initial savings (property) - they can be received by the individual at birth, inherited, or donated. In accordance with the general concept of the life cycle, the consumer will plan the consumption of this asset so as to ensure a uniform level of consumption throughout his life. In each current year of working life T individual's property v consists of initial property and accumulated savings. During the rest of his life, the consumer capabilities of the individual at the point in life T with property v, average annual labor income y, waiting to be processed ( Tr – T) years and live ( Tj – T) years will be

C* (Tj – T) =v+ (Tr – T) *y

Dividing this amount by the number of years of remaining life, we determine the volume of current consumption:

https://pandia.ru/text/78/121/images/image017_55.gif" width="246" height="58 src="> Tr > T

Where cv = 1 / (Tj - T)- marginal propensity to consume property;

cy ≡ (Tp – T) / (Tj – T)- marginal propensity to consume labor income.

It should be noted that marginal propensities to consume are related to the individual’s current position in the life cycle . The closer an individual is to the end of his life, the higher his propensity to consume property, and the marginal propensity to consume labor income depends not only on the number of years of remaining life, but also on the number of planned years of work.

The theory considered is a strictly microeconomic theory that explains the consumption and savings of individuals throughout life. If each participant in economic relations builds his consumption in this way, then aggregate consumption function similar to individual:

https://pandia.ru/text/78/121/images/image019_55.gif" width="143" height="48 src=">

Since the amount of wealth does not change strictly in proportion to annual income, it is obvious that in the short term the ratio of wealth to disposable income will change: it will fall when income increases and increase when it decreases. These fluctuations will lead to short-term changes in the average propensity to consume. In the long run, income growth means accumulation of wealth, therefore the ratio between wealth and income will remain constant and the average propensity to consume will not change.

A slightly different explanation for the fact that in short term the average propensity to consume fluctuates, while in the long run it remains constant, M. Friedman gave in his theories of permanent (constant) income

. Friedman proposed to consider current income as the sum of two components - permanent (permanent) income and temporary income. Permanent income is that portion of income that the consumer expects to continue into the future, while temporary income is not expected to continue into the future. In other words, permanent income is the weighted average income of a consumer during his lifetime, and temporary income is a random deviation from the average income. The concept of permanent income is based on the assumption that households strive to maintain consumption at a constant level, regardless of fluctuations in current income. In other words, household consumption depends on permanent income

because consumers can use their savings and debt to smooth out fluctuations in temporary income.

A slightly different explanation for the fact that in short term the average propensity to consume fluctuates, while in the long run it remains constant, M. Friedman gave in his theories of permanent (constant) income

. Friedman proposed to consider current income as the sum of two components - permanent (permanent) income and temporary income. Permanent income is that portion of income that the consumer expects to continue into the future, while temporary income is not expected to continue into the future. In other words, permanent income is the weighted average income of a consumer during his lifetime, and temporary income is a random deviation from the average income. The concept of permanent income is based on the assumption that households strive to maintain consumption at a constant level, regardless of fluctuations in current income. In other words, household consumption depends on permanent income

because consumers can use their savings and debt to smooth out fluctuations in temporary income.

When calculating permanent income, it is usually assumed that it is related to the behavior of current and past income. For example, you can estimate permanent income ( yp) as last year's income (y0 ) plus some portion of the change in current year income (y1 ) compared to the past:

yp = y0 + α (y1 – y0 ) = αy1 + (1 - α ) y0 ; 0 < α < 1,

Where α – the share of the change in the current year’s income compared to the previous year, added to the previous year’s income when calculating permanent income.

M. Friedman also proposes an assessment of permanent income using income for several previous periods, while the coefficients α increase as we move from more distant to closer periods. It should be noted that the coefficient α characterizes consumer expectations regarding the dynamics of their income. Usually he takes higher value, when income changes steadily, and, on the contrary, is low for those consumers whose income is subject to strong fluctuations.

In accordance with Friedman's hypothesis, the volume of current household consumption depends on permanent income and is determined by the formula

Ct = Ct (yp) = c * yp = c * α * yt + c * (1 – α) * yt-1.(2.3)

From here it is easy to understand that average propensity to consume

in the long run is constant and equal to the limit: C/y =c * (yp/y), while in the short term it may fluctuate depending on the change in current income compared to constant income (ratio yp/y). Because the marginal propensity to consume

current income is

c*α,

then it is clear that there is a difference between the short-run marginal propensity to consume and the long-run marginal (equal to average) propensity to consume ( c). This difference is explained by the fact that the individual is not confident in the constancy of his income growth and means that there are long-run and short-run consumption functions

.

Example . Let the consumer receive income y0 = 100 and y1 = $150 The marginal propensity to consume is c = 0.75, coefficient α = 0.8. Then:

· permanent income will be y = 100 + 0,8 (150-100) = 140;

· volume of consumption in the current period C = 0,75 * 0,8 * 150 + 0,75 *,8) * 100 = 90 + + 15 = 105;

· the marginal propensity to consume current income is equal to c * α = 0,75*0,8 = 0,6.

The concepts of life cycle and permanent income do not contradict each other, but are complementary. The life cycle theory pays more attention to the savings motive than the permanent income theory. And permanent income theory takes a closer look at the way individuals form expectations about future income.

The consumption functions discussed earlier are based on two premises: 1) income for the consumer is exogenously given; 2) when distributing income between consumption and savings, consumption is primary.

The consumption functions discussed earlier are based on two premises: 1) income for the consumer is exogenously given; 2) when distributing income between consumption and savings, consumption is primary.

In the neoclassical concept, the individual also makes decisions within the framework of long-term planning, but at the same time the individual’s income is not exogenously given for him . The individual determines the amount of income himself, distributing his available time between free and working. The decision on the distribution of time between free and working, as well as on the distribution of current income between consumption and savings, is subordinated to the task of maximizing the individual’s well-being in the long term. Moreover, in the neoclassical concept, saving is primary in relation to consumption: that is, the individual first of all determines the amount of necessary savings (necessary to ensure a certain level of consumption in the future), and only then forms his consumption as the remainder of income.

|

|

Loan interest" href="/text/category/ssudnij_protcent/" rel="bookmark">loan interest).

Thus, in the concept of the neoclassical school, the volume of free time, as well as the volume of household consumption, is a decreasing function of the interest rate, and savings is an increasing function.

General graphical representation neoclassical functions of consumption and savings are presented in Figure 2.3.

The simplest algebraic form of these functions is:

C (i) =Ca+YD –a*i– consumption function, (2.4 a)

S (i) = - Ca + a * i– savings function, (2.4 b)

Where Ca– volume of consumption independent of the interest rate;

YD- disposable income;

a- a parameter showing by how many units consumption will decrease (savings will increase) if the interest rate increases by one point.

2.1.2. Business sector demand

The demand of the business sector is determined by its demand for investment goods, which are necessary for entrepreneurs for two purposes: restoring worn-out capital and increasing real capital. Accordingly, the total investment volume (I) divided into restoration equal to depreciation (A) and net (net) investments (In). Economists distinguish three types of investment expenses: investments in fixed assets of enterprises; investment in housing construction; investment in inventories. To simplify the model, we will focus on the analysis of the first type of investment.

Investment demand is the most volatile part of aggregate demand. Investments react most strongly to changes in economic conditions, and, in turn, are often the cause of market fluctuations. The specificity of the impact of investments on the economic situation is that at the time of their implementation, the demand for goods increases, and the supply of goods will increase only after some time, when new production capacities come into operation.

Investments are called induced if they are caused by a sustainable increase in demand for goods

. When, at full utilization of production capacity, used with optimal intensity, the increased demand for goods increases and persists for a long period, it is in the interests of entrepreneurs to increase production capacity for the purpose of manufacturing additional products.

Investments are called induced if they are caused by a sustainable increase in demand for goods

. When, at full utilization of production capacity, used with optimal intensity, the increased demand for goods increases and persists for a long period, it is in the interests of entrepreneurs to increase production capacity for the purpose of manufacturing additional products.

To determine the volume of induced investments, it is used coefficient of incremental capital intensity of products (k), showing how many units of additional capital are required to produce an additional unit of output:

k = ∆ K / ∆ Y.

Given the incremental capital intensity to increase production from Y0 before Y1 induced investments are required in the amount

Iin = k (Y1 - Y0 ).

Thus, induced investment is a function of the increase in national income. With a uniform increase in national income, the volume of induced investment is constant. It should be noted that if in the current year the national income has decreased compared to the previous year ( Yt < Yt-1 ), then induced investments take a negative value. In practice, this means that due to a reduction in production, entrepreneurs do not partially restore worn-out capital, therefore the negative value of induced investments cannot exceed the amount of depreciation ( Iin ≤ - A).

The incremental capital intensity ratio is also called accelerator , and the calculation of induced investments – accelerator model.

It often turns out that it is profitable for entrepreneurs to make investments even with a fixed national income (for a given demand for goods). First of all, this is an investment in new technology and improving product quality. Such investments often themselves cause an increase in national income, but their implementation is not a consequence of an increase in national income, which is why they are called autonomous . Let's consider what factors determine the volume of autonomous investments.

According to the neoclassical concept, entrepreneurs make investments to bring the amount of available capital to an optimal size. The dependence of investment on the volume of operating capital can be represented by the formula:

According to the neoclassical concept, entrepreneurs make investments to bring the amount of available capital to an optimal size. The dependence of investment on the volume of operating capital can be represented by the formula:

![]() 0 <

β < 1,

(2.5)

0 <

β < 1,

(2.5)

where is the volume of investment for period t;

The amount of capital existing at the beginning of period t;

K* - optimal amount of capital;

β - coefficient characterizing the speed of approaching the existing volume of capital to the optimal one over the period t.

The determination of the optimal amount of capital is known from microeconomic analysis. The optimal amount of capital is one that provides maximum profit with existing technology and given prices of production factors. Under perfect competition, a firm earns maximum profit when the marginal productivity of capital ( r) is equal to the marginal cost of its use. The marginal productivity of capital can be defined as the increase in product y per additional unit of capital used:

The marginal cost of using capital (the cost of using an additional unit of capital) under conditions of perfect competition is determined by summing the interest rate on financial assets i(since the firm can either borrow capital or treat the loan as Alternative option use of equity capital) and depreciation rates d. So, with the optimal amount of capital, equality is achieved:

r = i + d,

or, if we ignore depreciation: r = i.

Thus, the optimal amount of capital for a company for a given volume of output depends on the marginal cost of using capital and its marginal productivity, determined by the technological parameters of production. After achieving the optimal amount of capital, firms will make autonomous investments only when the interest rate decreases or the marginal productivity of capital increases:

I = I (r, i).

If production technology and the marginal productivity of capital are constant, then the function of autonomous investment becomes a function of one variable - the interest rate: https://pandia.ru/text/78/121/images/image036_35.gif" alt="Signature :" align="left" width="193" height="80 src=">Дж. М.Кейнс, интерпретирует поведение инвесторов иначе. По его мнению, потенциальный инвестор сравнивает рыночную ставку процента не с производительностью и доходностью действующего капитала, а с потенциальной эффективностью планируемых инвестиционных проектов. !}

Since investments, in contrast to current production costs, produce results not in the current period, but in a number of subsequent periods, when comparing investment costs with the results obtained from them, the problem of measuring different time value indicators arises. This problem is solved by introducing a discount factor

(discount rate) δ

: the present value of the good that will be received through t years, assuming no inflation, is determined by dividing its value by the expression (1 +

δ

)

t. In its content, the discount rate is a measure of the preference of an economic entity for the current value of the future. As a rule, each individual has his own degree of preference. If the discount rate of an individual is less than the interest rate on deposits, then he will prefer to invest money in the bank. And vice versa - those who prefer to keep cash have a discount rate that exceeds the interest on deposits.

Example: Let a certain individual have the opportunity to receive $300 in a year, and his subjective discount rate is 0.5. In this case, the future 300 dollars for him will be equivalent to the opportunity to receive 300 / (1 + 0.5) = 200 dollars today. In other words, if an individual is faced with a choice: to receive 200 dollars today or 250 in a year, he will choose the first ( since 250 is less than 300). The choice between “today’s” 200 and “future” 350 dollars will be made in favor of the second option.

Similarly, when assessing the potential profitability of an investment project, capital investments must be compared not with the absolute value, but with the discounted value of the expected income. Let some investment project require K investments in the current period and promise to give P1, P2, P3 net income in the next three periods, respectively. The investor will consider this project economically feasible if

Cost of capital" href="/text/category/stoimostmz_kapitala/" rel="bookmark">cost of investment

does not equal the discounted income from the project. Since, for given levels of expected income, the value of discounted income depends on the value δ

, then the value δ

, at which inequality (2.6) becomes equality and the motive to invest disappears is called marginal efficiency of capital

(R) or internal profitability of an investment project.

To understand the economic meaning of the coefficient R Let's assume that the investment project is designed for 1 year. In this case, the marginal efficiency of capital is determined as follows:

https://pandia.ru/text/78/121/images/image039_30.gif" width="624" height="372">

i2

i1

Drawing 2.

4

.

Ranking of investment projects

according to their ultimate efficiency.

In addition to risky investments in real capital, an investor can invest his funds in securities or other property with a guaranteed return i (for example, government bonds). Therefore, the optimal volume of investment in real capital is found from the equality R (I) = i. In the case presented in Figure 2.4, with i1 investments will be made in the first four projects. If the interest rate increases to i2 , then only the first two will be implemented.

Thus, according to the Keynesian approach, investment will increase until there are no capital assets left whose marginal efficiency exceeds the current rate of interest. In other words, the volume of investment will tend to the point on the graph where R =

i. Indeed, if R <

i,

It is preferable for an investor to lend available funds to someone (or invest in securities

), than to invest them in production; Besides, in modern economy Most capital investments are made through borrowed funds, therefore, when R <

i borrowing funds to invest in real production becomes unprofitable. Thus, for a given marginal efficiency of investment projects R, the volume of investment in production is greater, the lower i and higher difference (R -

i)

.

So, the autonomous demand for investment in the Keynesian concept depends on the marginal efficiency of capital and the interest rate: Ia =Ia (R,i). If you accept dependence R (I) linear, this function can be represented explicitly by the formula

Ia = II * (Rmax - i),

Where II– marginal propensity to invest, which shows how many units the volume of investment will change when the difference between the marginal efficiency of capital and the current interest rate changes by one percentage point.

For a given set of investment projects II And Rmax are exogenous parameters and the volume of autonomous investments depends only on the interest rate: Ia = Ia (i).

The discrepancies between neoclassics and J.M. Keynes when describing investor behavior are due to the fact that r And R are different. Marginal productivity of capital ( r) characterizes the production technology used and is an objective parameter. Marginal efficiency of capital ( R) is a subjective category, so the values of future income ( Ri), determining the marginal efficiency of capital R, are expected values. They are based on the investor's assumptions about future prices, costs and demand. Therefore, in the Keynesian concept, the volume of investment significantly depends on the subjective views of the investor.

2.1.3. Aggregate demand

Private sector" href="/text/category/chastnij_sektor/" rel="bookmark">private sector, for production public goods. Since the economic activity of the state, unlike the activities of the private sector, does not have a clearly defined optimality criterion, it is difficult to identify the main factors that unambiguously determine the volume of government spending. Therefore, in macroeconomic modeling of a short period G is considered as an exogenous quantity, that is, the state demand function in the goods market has the form G=const. In addition to the direct impact of the state on the market of goods through their purchase, it has an indirect impact on aggregate demand through taxes and loans. Taxes change the amount of disposable income of households, and government loans are reflected at the level of the real interest rate, therefore, on the investment demand of entrepreneurs.

Demand abroad in the market for the goods of a certain country, in the Keynesian concept it is determined by the amount of national income abroad, and in the neoclassical concept - by the foreign interest rate. The volume of a country's foreign trade also significantly depends on the ratio of prices for domestic and foreign goods and the exchange rate. We will assume that all the above quantities are constant, therefore: NE =const.

The aggregate supply" href="/text/category/sovokupnoe_predlozhenie/" rel="bookmark">the aggregate supply of goods, which requires additional research. Therefore, at this stage We will proceed from the assumption that at a fixed price level, the supply of goods is completely elastic, that is, entrepreneurs at a given price level are always ready to offer as many goods as they are asked for. In practice, a similar situation occurs during periods of underemployment, when entrepreneurs can increase output by additionally attracting labor without increasing average production costs. Such assumptions regarding aggregate supply are characteristic of the Keynesian understanding of macroeconomic processes, therefore our further analysis of equilibrium in the goods market within the framework of this topic relates entirely to Keynesian model of macroeconomic equilibrium .

23. Market demand of households and factors determining its changes.

24. Market supply and factors determining its change.

The solution to these problems is mainly undertaken by the state, becoming a participant in not only political but also economic relations.

The behavior of a household as a consumer is influenced by many factors, in particular preferences, the amount of income received, the price level for consumer goods, and the volume of property. Their totality determines the individual demand of an individual farm, which is a component of market demand.

A change in income leads to an increase in the financial capacity of the household. According to the assumption of rational behavior, it should look for a new optimal set that corresponds to new financial opportunities. When studying the effect of changes in income on the demand for a particular good, three main types of consumer reactions are distinguished.

First, it is possible that demand will change in the same direction as the change in income. It is likely to assume that with an increase in income, the vast majority of households will have an increase in demand for some goods, for example, clothing, and with a decrease, vice versa. Goods that exhibit such a consumer reaction are called goods of high consumer quality. Secondly, the demand for a particular good changes in the opposite direction relative to changes in income. In other words, as income increases, the demand for some goods, for example bread, decreases (this is understandable, since consumers switch their consumer demand to goods that better satisfy their needs, and when it decreases, on the contrary, it increases. Goods that exhibit such a consumer reaction , are called goods of low consumer quality.

Thirdly, the demand for some goods may be characterized by the absence of a response of demand to changes in income (within certain limits). An example of such benefits could be transport services if, as income increases, consumers continue to use the same types of urban transport as before, rather than taking, say, a taxi.

Market supply- supply of goods by all sellers on the market. The main indicators of supply are the supply volume and price. Supply volume- this is the quantity of goods that sellers are willing to sell. Offer price is the minimum price at which sellers agree to sell a certain quantity of goods.

Market supply factors:

1. Prices for resources. They can either stimulate an increase in supply (if they are decreasing) or hinder this (if they are growing).

2. Changes in production technology. Improvements in technology make it possible to produce a unit of product at a lower cost, which leads to lower production costs and increased supply.

3. Taxes and subsidies. Taxes increase production costs and reduce supply. Subsidies lower production costs and increase supply.

4. Prices for other goods. Changes in prices for other goods lead to a spillover of resources (firms leaving for other industries). The departure of producers reduces the supply of goods.

5.Expectations. Expectations of changes in the price of a product in the future may affect the manufacturer's desire to supply it to the market at the present time.

6.Number of sellers. For a given volume of production in each firm, than larger number suppliers, the greater the market supply.

7.Natural conditions: natural disasters, damaging the economy, reduce supply.

4. Main factors influencing household demand

Household demand is influenced by a combination of factors, among which the most significant are preferences, income, prices, and the volume of household property.

A change in income leads to a change in the budget constraint: if income increases, then there is a parallel upward shift in the budget line; if it decreases, down. In accordance with this, the individual will move to consumption plans that are different from the original ones. The curves transferred to a separate graph, reflecting the dependence of the demand for a particular good on the amount of income, are named after the scientist who first did this, Engel curves. There are three possible types of consumer reaction to a change in income: a) a change in the volume of consumption of a good in the same direction; b) a change in the volume of consumption of a good in the opposite direction; c) lack of demand response to changes in income. In accordance with the first two types of reaction, households distinguish between higher and lower goods.

The highest goods are understood as those for which the volume of demand for which increases with an increase in income, and decreases with a decrease. A typical example would be goods that satisfy spiritual needs.

By inferior goods we mean goods, the volume of demand for which decreases with an increase in income, and increases with a decrease. These are, for example, goods that satisfy physical (especially physiological) needs, such as the need for certain types of food.