Ice battle or battle on Lake Peipsi- the battle of the Novgorod-Pskov army of Prince Alexander Nevsky with the troops of the Livonian knights, which took place on April 5, 1242 on the ice of Lake Peipsi. It put a limit to the advance of German knighthood to the East. Alexander Nevsky - Prince of Novgorod, Grand Duke Kiev, Grand Duke of Vladimir, legendary commander, saint of the Russian Orthodox Church.

Causes

In the middle of the 13th century, Russian lands were threatened from all sides by foreign invaders. The Tatar-Mongols were advancing from the east, and the Livonians and Swedes were laying claim to Russian soil from the northwest. In the latter case, the task of fighting back fell to powerful Novgorod, which had a vested interest in not losing its influence in the region and, most importantly, in preventing anyone from controlling trade with the Baltic countries.

How it all began

1239 - Alexander took measures to protect the Gulf of Finland and the Neva, which were strategically important for the Novgorodians, and therefore was ready for the Swedish invasion in 1240. In July, on the Neva, Alexander Yaroslavich, thanks to extraordinary and swift actions, was able to defeat the Swedish army. A number of Swedish ships were sunk, but Russian losses were extremely insignificant. After that, Prince Alexander was nicknamed Nevsky.

The Swedish offensive was coordinated with the next attack of the Livonian Order. 1240, summer - they took the border fortress of Izborsk, and then captured Pskov. The situation for Novgorod was becoming dangerous. Alexander, not counting on help from Vladimir-Suzdal Rus', devastated by the Tatars, imposed large expenses on the boyars in preparation for the battle and tried to strengthen his power in the Novgorod Republic after the victory on the Neva. The boyars turned out to be stronger and in the winter of 1240 they were able to remove him from power.

Meanwhile, German expansion continued. 1241 - the Novgorod land of Vod was imposed with tribute, then Koporye was taken. The Crusaders intended to capture the coast of the Neva and Karelia. A popular movement broke out in the city for an alliance with the Vladimir-Suzdal principality and the organization of resistance to the Germans, who were already 40 versts from Novgorod. The boyars had no choice but to ask Alexander Nevsky to return. This time he was given emergency powers.

With an army of Novgorodians, Ladoga, Izhorians and Karelians, Alexander knocked out the enemy from Koporye, and then liberated the lands of the Vod people. Yaroslav Vsevolodovich sent the Vladimir regiments, newly formed after the Tatar invasion, to help his son. Alexander took Pskov, then moved to the lands of the Estonians.

Movement, composition, disposition of troops

The German army was located in the Yuryev area (aka Dorpat, now Tartu). The Order gathered significant forces - there were German knights, the local population, and the troops of the King of Sweden. The army that opposed the knights on the ice of Lake Peipus had a heterogeneous composition, but a single command in the person of Alexander. The “lower regiments” consisted of princely squads, boyar squads, and city regiments. The army that Novgorod fielded had a fundamentally different composition.

When the Russian army was on the western shore of Lake Peipus, here in the area of the village of Mooste, a patrol detachment led by Domash Tverdislavich scouted out the location of the main part of the German troops, started a battle with them, but was defeated. Intelligence managed to find out that the enemy sent minor forces to Izborsk, and the main parts of the army moved to Lake Pskov.

In an effort to prevent this movement of enemy troops, the prince ordered a retreat to the ice of Lake Peipsi. The Livonians, realizing that the Russians would not allow them to make a roundabout maneuver, went straight to their army and also set foot on the ice of the lake. Alexander Nevsky positioned his army under the steep eastern bank, north of the Uzmen tract near the island of Voroniy Kamen, opposite the mouth of the Zhelcha River.

Progress of the Battle of the Ice

The two armies met on Saturday, April 5, 1242. According to one version, Alexander had 15,000 soldiers at his disposal, and the Livonians had 12,000 soldiers. The prince, knowing about the German tactics, weakened the “brow” and strengthened the “wings” of his battle formation. Alexander Nevsky's personal squad took cover behind one of the flanks. A significant part of the prince's army was made up of foot militia.

The crusaders traditionally advanced with a wedge (“pig”) - a deep formation, shaped like a trapezoid, the upper base of which was facing the enemy. At the head of the wedge were the strongest of the warriors. The infantry, as the most unreliable and often not at all knightly part of the army, was located in the center of the battle formation, covered in front and behind by mounted knights.

At the first stage of the battle, the knights were able to defeat the leading Russian regiment, and then they broke through the “front” of the Novgorod battle formation. When, after some time, they scattered the “brow” and ran into a steep, steep shore of the lake, they had to turn around, which was quite difficult for a deep formation on the ice. Meanwhile, Alexander’s strong “wings” struck from the flanks, and his personal squad completed the encirclement of the knights.

A stubborn battle was going on, the entire neighborhood was filled with screams, crackling and clanging of weapons. But the fate of the crusaders was sealed. The Novgorodians pulled them off their horses with spears with special hooks, and ripped open the bellies of their horses with “booter” knives. Crowded together in a narrow space, the skilled Livonian warriors could not do anything. Stories about how the ice cracked under heavy knights are widely popular, but it should be noted that a fully armed Russian knight weighed no less. Another thing is that the crusaders did not have the opportunity to move freely and they were crowded into a small area.

In general, the complexity and danger of conducting combat operations with cavalry on the ice in early April leads some historians to the conclusion that the general course of the Battle of the Ice was distorted in the chronicles. They believe that no sane commander would take an iron-clanging and horse-riding army to fight on the ice. The battle probably began on land, and during it the Russians were able to push the enemy onto the ice of Lake Peipsi. Those knights who were able to escape were pursued by the Russians to the Subolich coast.

Losses

The issue of the losses of the parties in the battle is controversial. During the battle, about 400 crusaders were killed, and many Estonians, whom they recruited into their army, also fell. The Russian chronicles say: “and Chudi fell into disgrace, and Nemets 400, and with 50 hands he brought them to Novgorod.” The death and capture of such a large number of professional warriors, by European standards, turned out to be a rather severe defeat, bordering on catastrophe. It is said vaguely about Russian losses: “many brave warriors fell.” As you can see, the losses of the Novgorodians were actually heavy.

Meaning

The legendary massacre and the victory of Alexander Nevsky’s troops in it were of exceptional importance for the entire Russian history. The advance of the Livonian Order into Russian lands was stopped, the local population was not converted to Catholicism, and access to the Baltic Sea was preserved. After the victory, the Novgorod Republic, led by the prince, moved from defensive tasks to the conquest of new territories. Nevsky launched several successful campaigns against the Lithuanians.

The blow dealt to the knights on Lake Peipus was echoed throughout the Baltic states. The 30 thousand Lithuanian army launched large-scale military operations against the Germans. In the same year 1242, a powerful uprising broke out in Prussia. The Livonian knights sent envoys to Novgorod who reported that the order renounced its claims to the land of Vod, Pskov, Luga and asked for an exchange of prisoners, which was done. The words that were spoken to the ambassadors by the prince: “Whoever comes to us with a sword will die by the sword” became the motto of many generations of Russian commanders. For his military exploits, Alexander Nevsky received the highest award - he was canonized by the church and declared a Saint.

German historians believe that, while fighting on the western borders, Alexander Nevsky did not pursue any coherent political program, but successes in the West provided some compensation for the horrors of the Mongol invasion. Many researchers believe that the very scale of the threat that the West posed to Rus' is exaggerated.

On the other hand, L.N. Gumilyov, on the contrary, believed that it was not the Tatar-Mongol “yoke”, but rather Catholic Western Europe in the person of the Teutonic Order and the Archbishopric of Riga that posed a mortal threat to the very existence of Rus', and therefore the role of Alexander’s victories Nevsky is especially great in Russian history.

Due to the variability of the hydrography of Lake Peipsi, historians for a long time could not accurately determine the place where the Battle of the Ice took place. Only thanks to long-term research carried out by an expedition from the Institute of Archeology of the USSR Academy of Sciences, they were able to establish the location of the battle. The battle site is submerged in water in the summer and is located approximately 400 meters from the island of Sigovec.

Memory

The monument to the squads of Alexander Nevsky was erected in 1993, on Mount Sokolikha in Pskov, almost 100 km away from the actual site of the battle. Initially, it was planned to create a monument on Vorony Island, which would have been a more accurate solution geographically.

1992 - in the village of Kobylye Gorodishche, Gdovsky district, in a place close to the supposed site of the battle, a bronze monument to Alexander Nevsky and a wooden worship cross were erected near the Church of the Archangel Michael. The Church of the Archangel Michael was created by the Pskovites in 1462. The wooden cross was destroyed over time under the influence of unfavorable weather conditions. 2006, July - on the 600th anniversary of the first mention of the village of Kobylye Gorodishche in the Pskov Chronicles, it was replaced with a bronze one.

The German knights-crusaders, who knew the strength of the leadership talent and authority in Rus' of the young Novgorod prince Alexander Yaroslavich, gathered a huge army at that time to defeat the no less formidable Russian army. In fact, this was the second crusade against Novgorod Rus' after the campaign of the knightly army of the Kingdom of Sweden. The failure of the Swedes on the banks of the Neva did not cause any particular concern among the leadership of the Livonian Order, since it had a truly strong military organization on the day of the Battle of the Ice. The Russian land had not yet experienced the full power of the Livonian crusader knighthood.

Such a decisive clash of opponents took place on the ice of Lake Peipsi. The advantage of the Russian army was that its commander personally chose a convenient position for battle at the very edge of the coastline. There were winter roads - winter roads - leading from the Estonian coast to the Pskov and Novgorod regions. Near the shore there was a rock called Raven Stone. Nowadays, the remains of this rock are hidden by the waters of the lake and were discovered by archaeologists about two kilometers north of Cape Sigovets, washed by the waters of Lake Peipsi and the Samolva River.

From ancient times, Raven Stone served as a guard post for Pskov border wanderers, since in winter Livonian knights often went on raids along the winter roads - the road was straight and well-trodden. Therefore, the rock, towering above the water surface, became an observation post for the commander of the Russian army before the Battle of the Ice.

Domestic chronicles and chronicles of the opposing side did not convey to us data on the number of opposing forces on that day. Many researchers believe that up to 30 thousand people took part in the battle, a figure that is simply huge by European standards. The number of Russian soldiers is estimated at 15-17 thousand, the troops of the German Order - at 10-12 thousand. There is no chronicle evidence of these figures. The researchers made their calculations based on the general capabilities of their opponents.

The combat position chosen by Prince Alexander Nevsky perfectly constrained the maneuverability of the heavy knightly cavalry, which in battle had a powerful ramming blow. This gave an advantage to the Russian army, which mostly consisted of foot militias - Novgorodians and Pskovites. Although the mounted Novgorod militia and the mounted squads of the Vladimir and Suzdal residents were not much inferior to the enemy.

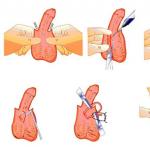

Russian horsemen were well protected from blows by metal chain mail with sleeves tied at the wrists with metal hoops. They wore pointed helmets on their heads, unlike the German round helmets. The iron “motina” - the chainmail mesh - was no worse than a knight’s visor. Rich warriors also had chain mail stockings. The hands were protected by combat gloves with metal plates sewn onto them. The weapons included swords, spears, shields, bows, crossbows, battle axes, clubs, flails...

The militias from the simple, Novgorod people - “howl” - were noticeably worse armed. They simply couldn’t afford expensive armor. Their shields were, as a rule, wooden, with metal plates stuffed on them. When getting ready for battle, the “howls” armed themselves with spears, swords, bows and arrows, axes, sometimes mounted on long axes, flails, or even just strong clubs. Most of the Novgorod foot militia “warriors” were armed at the expense of the free city.

The German crusading knights had excellent military equipment. The people and their horses were clad in steel armor - in armor - as they say, from head to toe. The armor of the order's brother-knight consisted of a shield, armor, chain mail, a strong iron helmet with narrow slits for the eyes and small holes for breathing, iron gloves and chain mail stockings or steel leggings. An iron chain mail blanket also covered the chest and sides of the war horse. His head was sometimes covered with steel.

The crusading knights were armed with long and heavy swords, the handles of which in many cases made it possible to fight with two hands, heavy spears bound in iron, equally heavy maces with sharp spikes, battle axes, long daggers... Their squires were slightly worse armed than the knights themselves. and servants. Their combat equipment differed only in the quality of armor and weapons and their price. The majority of foot bollard warriors were armed with short swords, crossbows, spears...

German knights, professional warriors, were reputed in Europe to be very experienced in warfare. They were well organized, bound by mutual responsibility and the blessing of the Pope. The main force of European chivalry, and not just the Livonian Order, was the heavy cavalry clad in steel armor. Each knight was such a well-armed and trained mounted warrior that in battle he alone was worth several enemy fighters. The knight's cavalry became even more terrible when it delivered a powerful ramming blow to the enemy ranks.

The order of battle of the knightly army of the German order was not a big secret for the Russians. The knights advanced with an “iron wedge”, a “boar’s head” or, as it is called in Russian chronicles, a “pig”. The right flank of such an “iron wedge” was the most dangerous. The tip of a boar's head was usually used to tear the ranks of enemy troops into two unequal halves.

In fact, the “pig” was a trapezoid - that is, a blunt, truncated deep column in the form of a wedge. In her head, at the forefront of the blow, three to five of the most experienced and skillful mounted knights stood. In the second rank there are five to seven knights. All subsequent rows of the "boar's head" increased by two people in each row. Thus, the result was a column of iron-clad warriors and their war horses, which rammed the enemy formation on the move.

The head of the “pig” was headed by the patricians of the order - commanders and the most distinguished warriors in battle. Behind them, under reliable guard, were the order's bannermen. It was believed that while the banner was flying over the knightly army, none of the order brothers, according to the charter, had the right to leave the battlefield. In case of loss of the banner there was a spare one. It was intended to at least somehow keep the crusaders from fleeing in case of failure to start the battle.

Prince Alexander Nevsky arranged the battle formations of his army in a “regimental row” for the best use of all the advantages of such a formation against the knightly army. This in itself testified to the great military leadership talent of the ancient Russian commander, who was well versed in the tactical art of the order’s military leaders.

Archers and crossbow shooters were sent forward. According to the German “Rhymed Chronicle”, there were many Russian shooters. When a reconnaissance detachment of Livonian knights approached the location of the Russian army, they drove it away, shooting from long-range bows. Before the Battle of the Ice, the Order's leadership failed to reconnoiter the enemy's battle formation on the opposite shore of Lake Peipsi.

The most important thing was done even before the start of the battle - the crusaders were unable to establish the location of the formation of the Russian heavy cavalry - the princely squad, the cavalry squads of the Suzdal and Vladimir warriors, and the Novgorodians. Otherwise, the direction of the “pig” strike could have been different.

Behind the archers, located in the first battle line, was an advanced regiment, consisting of foot soldiers and having many archers in its ranks. The task of the advanced regiment was to, as far as possible, disrupt the ranks of the “boar’s head” of the crusader army going to ram. After this, the leading regiment fought back to its main forces.

Behind the forward regiment there was a large regiment called “chelo”. He was also on foot and the most numerous in terms of the number of warriors. The main burden of hand-to-hand combat at the beginning of the battle fell on the “brow”. The most experienced and persistent commander was placed at the head of a large regiment.

On the flanks of the “brow” - its “wings” - regiments of the right and left hands were lined up. Researchers believe that their basis was cavalry, well trained and armed. The wings were also reinforced by foot soldiers, who, first of all, had good weapons. Flanking foot detachments strengthened the horse squads. In the combat position of the Russian army at the Crow Stone, the prince-warrior’s plan for the upcoming battle was clearly visible - to cover the knight’s “pig” from the sides with strong wings.

In the rear, near the very steep bank, overgrown with forest, a sleigh train may have stopped. There was shallow water here and dry reeds stuck out from under the snow. Some researchers believe that it was behind the “brow” that Prince Alexander Nevsky placed his squad, which was to take on the weakening ramming blow of the knight’s “boar’s head”, cutting a large regiment in half.

The chronicle sources do not contain any information about the ambush regiment, an indispensable element of the combat formation of the Russian army of that era. Although many researchers believe that the ambush regiment in the Battle of the Ice was most likely mounted, small in number and consisting of well-trained and disciplined princely warriors. An ambush strike at the decisive moment of a battle in the distant historical past more than once brought victory to Russian weapons.

It can be considered that a strong ambush regiment dealt a decisive blow to the crusaders during the battle on the ice of Lake Peipsi. Prince Alexander Nevsky, who perfectly studied the military art of Rus', it seems, simply could not refuse the benefit strong blow cavalry attacking from an ambush. Moreover, during the Battle of the Ice, it was not the Russian army that attacked the enemy, but the army of the Livonian Order.

There are other opinions as to whether the Russians had or did not have a strong ambush regiment that day. Indeed, the coastline near the Crow Stone did not allow a detachment of mounted warriors in large numbers to take refuge. The dense forest covered in deep snow that approached the shore did not allow this to be done. Based on this, it can be argued that if there was an ambush regiment, it consisted of a small number of mounted warriors.

It was no coincidence that the young Novgorod prince built the center of his battle formations from infantry. It wasn't even a matter of its quantitative superiority over the cavalry. In Rus', the foot army always consisted of urban and rural militias and, unlike Europe, was not considered a secondary branch of the army. Regiments of foot warriors skillfully interacted with mounted squads, as the Battle of the Neva showed, and in many cases could decide the outcome of large and small battles.

The order's command, building its plan for the upcoming battle with the army of the free city of Novgorod and its allies, decided with the very first blow of the “iron wedge” to crush the center of the enemy’s battle formation and cut it in two. Such proven tactics more than once brought convincing success and complete victory to the Order brothers in wars against the Baltic peoples. Therefore, this time the German knights built a terrifying “pig” with just their appearance.

Prince Alexander Nevsky's battle plan was simple and clear to his commander. The knightly “pig” had to lose the power of its ramming blow, fighting against the advanced and large regiments, bury itself in the coastline and lose its move there. After this, the “wings” of the Russian army covered the enemy wedge from the sides and began to smash it. The “pig,” according to the commander’s plan, was bound to get bogged down in dense formations of foot warriors. Just in case, the stability of the center was reinforced by a crowd of baggage sleighs, which could become an insurmountable obstacle for the heavy knightly cavalry.

The knightly army emerging from the Estonian shore onto the ice of Lake Peipus was noticed by the sentries on the top of the Crow Stone from afar. Prince Alexander Yaroslavich, together with his close people, could observe how an impressively sized “pig” began to line up, which moved straight towards the Russian regiments, accelerating the horse’s running, thereby gaining ramming power.

From the height of the cliff, the Novgorod prince observed the movement of the troops of the German order and could appreciate their organization and discipline, and the orderliness of their battle formations. The enemy army, glittering with armor from afar, was clearly visible on snowy ice, inexorably approaching the Raven Stone, on top of which the frosty wind fluttered the princely banner.

What did the hero of the Battle of the Neva change his mind about, what did he feel in those moments? A deep consciousness of one’s own rightness, the impossibility of any concession to the crusading enemies, the “Latins”, who encroached on the freedom of Novgorod Russia, on the Orthodox faith, on everything that is dear to a free person in the Fatherland, the thought of the disasters that enemies have already caused to the Russian land, about the proud claims of the German knights - all this flashed with the speed of lightning in the mind of the illustrious descendant of Vsevolod the Big Nest.

Chroniclers will say, describing the last minutes of anticipation of an enemy strike, that as if from the depths of the soul, Prince Alexander Nevsky burst out an exclamation that was heard by many soldiers in the silent ranks of the Russian army:

Judge, O God, my dispute with this arrogant people! - he said loudly, raising his hands to the cloudy sky. - Help me, Lord, as once my great-grandfather Yaroslav did against Svyatopolk the Accursed!

In response to these exclamations of the great warrior, the answering exclamations of ordinary soldiers were heard from the nearby ranks of the lined up regiments:

O our dear and honest prince! It's time to! We will all lay down our heads for you!

On the day of the Battle of the Ice, the morale of the Russian army was unusually high. It is no coincidence that the chronicler notes that “Alexander had many brave, strong and strong; and being filled with the spirit of war, I beat their hearts like a sword.” That is, the hearts of Russian warriors beat in battle like lions.

Before the decisive battle, the warriors swore to their commander to lay down their heads for him and for Rus'. The regiments held a traditional prayer service before the battle. Prince Alexander Yaroslavich, together with simple warriors, asked the Almighty to help them, to grant victory to Russian weapons. The chronicler will say about this - “from the eloquent tongue, free me and help me.”

The course of the famous battle on April 5, 1242 on the ice of Lake Peipus - the Battle of the Ice - is reported in such ancient Russian chronicles as the Novgorod first of the older and younger editions, the Sofia first, Simeonovskaya... And the German Rhymed Chronicle - the Elder Livonian Rhymed Chronicle.

The battle began on Saturday at sunrise. Under the rays of the rising winter sun, sparkling the snow and ice, a wedge-shaped formation of the German knightly army opened before the eyes of the Russian soldiers, inexorably advancing on the Russian ranks.

The movement of the order's army was in the nature of a psychological attack. The iron “pig” approached the Russian formation slowly at first, so that the foot warriors-bollards could keep up with the mounted knights. The knights rode across the surface of Lake Peipsi astride war horses clad in armor, like themselves. The crusaders moved forward in the complete silence of the icy desert of the frozen lake. Banners fluttered above the “pig.”

Such a wedge-shaped formation of attacking knightly cavalry has always been terrible for a weak-willed army, which it cuts and crushes into small pieces, like a coastal rock cutting through sea waves. The scattered enemy, losing all contact and at the same time presence of mind in battle, often quickly fled. But the regiments of Prince Alexander Yaroslavich turned out to be different on that memorable day for the history of our Fatherland.

The picture of the Battle of the Ice, terrible in its bloodshed and tenacity, was captured for posterity by an ancient Russian chronicler - he wrote it down from the words of a participant in the battle - a “witness”. In all likelihood, this was not a simple princely warrior or a Novgorod militiaman.

The Russian soldiers clearly saw an iron wall rolling towards them across the ice, dotted with spots of the first thawed patches. Above her, spears that had not yet been lowered forward swayed menacingly, glittering in the rays of the rising sun. In the front rows of the Livonian “pig” banners with crosses sewn on them waved. Inside the iron wedge, a large crowd of foot bollards could be discerned, hurrying after the horsemen.

The first five at the head of the “pig” were led by the experienced knight Siegfried von Marburg, known for his strength and fury in battle. As they approached the Russian ranks, the crusading horsemen began to trot. The wedge, skillfully led by von Marburg, aimed at the very center of the enemy's battle formation.

Scattered in front of the advanced regiment, which consisted mainly of spearmen, archers and crossbow shooters began to shoot at extreme distance knights in white cloaks with ominous crosses sewn on them. Hundreds of arrows flew towards the attacking “pig”. But such a shower of arrows was of little use - they did not pierce the massive, solid armor of the German knights. The arrows slid along the steel and lost their destructive power. There is no information in the chronicles that the knightly cavalry on the approach to the opposite shore of Lake Peipsi suffered from Russian arrows.

The shooters began to hastily retreat to their own, trying to shoot a few more red-hot arrows into the enemy formation. The measured noise of the approaching enemy was suddenly split by the sound of trumpets playing the signal for the start of the attack of the Russian army. The knights, having given spurs to their horses, began to trot. The iron-clad spears of the mounted crusaders, as if on command, sank forward in a single moment.

With a terrible crash of metal on metal, the “iron wedge” crashed into the formation of the leading regiment, whose first ranks bristled with hundreds of spears. A bloody battle began, where no one spared each other. The silence around Crow Stone was suddenly swallowed up by the noise of a fierce battle - only the clanging of iron, the frenzied cries of people fighting in hand-to-hand combat, the groans of those struck by a sword or spear, the neighing of horses, the sounds of trumpets were heard...

It is unlikely that Prince Alexander Nevsky expected a different outcome at the beginning of that great battle. The “iron wedge”, step by step, of the knight’s horses pressed through the center of the advanced regiment, inexorably cutting it in two. Then the same fate befell the large regiment - the “chelo”. The chronicler, from the words of a “self-witness”, writes with bitterness about the beginning of the Battle of the Ice: “I ran into a regiment of Germans and people and knocked a pig through the regiment...”

But at the very steep shore, in the icy snowdrifts, among the snow-covered reeds, the blow of the “iron wedge” was taken by the Russian cavalry squad, which was not inferior in weapons and protective armor to the Order brothers. And besides, the steep bank did not allow mounted knights to ascend to Pskov land. Here the “pig’s snout” immediately became “dull.”

The majority of German knights had long ago broken their spears on Russian armor and under the blows of swords and axes. Many of the Livonians now fought with two-arshine (about 1.5 meters) two-handed heavy swords, the blow of which cut through helmets and shields. There were almost no spears in the hands of the Russian warriors either - swords, maces, axes flashed... The grinding of metal on metal began to drown out all other sounds of battle.

Soon, foot bollards entered the battle, hurrying after the “pig’s” head. They performed not only the role of infantry, but also served the mounted knights fighting in front during hand-to-hand combat. The success of the actions of the knightly cavalry largely depended on its interaction with the bollards. The knight, knocked out of the saddle, could not climb onto his horse on his own, and in this case Livonian foot soldiers came to his aid.

Riders knocked off their horses fell under the hooves of the horses, which trampled the wounded. The avalanche of iron-clad crusading knights immediately slowed down under the wooded shore in their terrifying ramming run. And the most important thing happened, on which Prince Alexander Nevsky pinned his hopes - the “iron pig” lost room for maneuver during a fierce battle.

Below the shore, the knightly cavalry army found itself sandwiched in a dense mass of Russian infantry, which did not even allow the horses to turn around. Close hand-to-hand combat ensued - knights in heavy armor and with heavy weapons in their hands hardly fought off the foot Russian warriors, who were not burdened with metal and had much lighter weapons. The crusaders were struck with spears and axes, pulled from their horses and finished off on the ice, and crushed with heavy clubs.

Now the German knights found themselves defending themselves from an enemy attack. They look around and through the slits of their helmets see with horror that instead of the expected disordered ranks, a living wall of warriors has stood in front of them. The menacing gaze of the Russians, the shine of their devastating weapons, their fury in hand-to-hand combat began to confuse the hearts of the crusaders. They had not met such an enemy for a long time in their campaigns of conquest.

Prince Alexander Nevsky did not wait long for this psychological turning point in the ranks of the fighting that morning. At a sign from his hand in a combat glove, now in the Russian camp, trumpets began to sing invitingly on Crow Stone. The regiments answered them with horns and beat tambourines. The princely banner of the Yaroslavichs with the image of the mighty king of beasts - a rearing lion - flew high.

Seeing that the knightly battle formation had completely broken down and lost its striking power, the winner in the Battle of the Neva began to decisively take the initiative of action into his own hands. Now he was leading the course of the battle according to his own scenario, predetermining the outcome of the Battle of the Ice.

The “iron pig” was hit from right and left by Russian cavalry, the “wings” of the Russian army. One of them was headed by brother Novgorod Prince Andrei Yaroslavich. The Vladimir-Suzdal cavalry regiments, the Novgorod cavalry, and the Ladoga residents went into battle together.

Although the chronicler, from the words of the “self-witness,” does not mention such an episode of the battle, it seems that at the most decisive moment the selected personal squad of the Novgorod prince himself, led by himself, rushed into battle. Led by an experienced leader, the princely equestrian warriors struck at the “pig’s” most vulnerable spot, going at full gallop to its rear, where only a single line of mounted order brothers covered the foot warriors-bollards.

Now more and more armored knights in white cloaks with large black crosses on them fell onto the ice. Where just a few minutes ago rows of mounted German knights towered above the Russian foot soldiers, their scattered groups were now visible. The Livonians, with their last strength, fought off the foot militias attacking them and the Russian horsemen who had just entered the battle.

An ancient Russian chronicler will tell his descendants with delight: “There was a great slaughter here, a slaughter of evil, and there was a terrible roar - a crack (crack) from the breaking spears and the sound from the cutting of a sword... and you couldn’t see the ice, covered for fear of blood.” And that the noise of the battle was like “the sea moving in a disgusting way.”

After stubborn resistance from the knights, the Russian warriors completely disrupted the ranks of the “iron pig”. The Livonian crusaders, clumsy in the saddle, were dragged or knocked off their horses onto the ice and there they were finished off. In heavy armor, the knights found themselves completely defenseless, being thrown onto the ice. Heavy armor prevented them from even just standing on their feet. Hand-to-hand combat with a discordant, although numerous, crowd of foot bollards ended very quickly. The chronicles will unanimously say that the “chud”, forcedly called into the ranks of the order’s army, in the Battle of the Ice showed neither persistence nor desire to die “for the cause” of its conquerors - the German knights. The bollards quickly fled in droves, trying to find salvation on the Estonian shore of Lake Peipsi.

The chronicler of the German Rhymed Chronicle, who is well acquainted with the course of the Battle of the Ice, will say with undisguised sorrow about the defeat of the German crusading knights:

“...Those who were in the army of the brother knights were surrounded,

The brother knights defended themselves quite stubbornly, but they were defeated there...”

The Order brothers really stubbornly defended themselves - after all, they were professional warriors. The knighthood of the German Order has always been distinguished by discipline and obedience to its master and his assistants. But when thousands of foot bollards, throwing away their weapons, shields and helmets as they went, ran from the icy battlefield, the noble patrician knights themselves turned their horses behind them. For the sake of illusory salvation, they also began to throw heavy shields, swords, maces, and combat gloves as they walked.

At the end of the battle, it began to seem to the crusading conquerors, as the Livonian Chronicle testifies, that each of them was attacked by at least 60 people from the Russian army. Such an obvious exaggeration of the German chronicler is not accidental: for the first time, the German order encountered a worthy opponent in its victorious advance to the East, who had an advantage where the Livonians did not expect it at all.

In the poem “Battle on the Ice,” the poet Konstantin Simonov, turning to the distant past of his native country, describes the climax of the battle on April 5, 1242 on the bloody ice of Lake Peipsi:

And, retreating before the prince,

Throwing spears and shields,

The Germans fell from their horses to the ground,

Raising iron fingers.

The bay horses were getting excited,

Dust kicked up from under the hooves,

Bodies dragged through the snow,

Stuck in narrow stirrups.

In vain that day, the commander of the order’s army, Vice-Master Andreas von Velven, tried to delay the flight of his knights, stop the faltering bollards and direct them to support the still fighting Livonians. However, it was all in vain: one after another, the order’s battle banners fell onto the ice, thereby spreading panic in the knightly ranks. The Crusaders lost the decisive battle against Novgorod Rus' outright.

Flight in the ranks of the crusader army became universal. The surrounded knights began to throw down their weapons and surrender to the mercy of the victors. But they did not give mercy to everyone - the order brothers did too much trouble on Pskov and Novgorod soil.

Fleeing from their pursuers, the crusading knights were ready to jump out of their heavy armor and run away. Those few crusaders who managed to escape from the encirclement did not see much hope for salvation. They were simply far from it - to the opposite Sobolichsky shore it was almost seven kilometers of escape on slippery ice, covered in places with water.

The chase began for the crusaders fleeing the battlefield. Horse warriors and Novgorodians pursued crowds of bollards and German knights who escaped “from the embrace” of the Russian army all the way to the Estonian coast. Having overtaken them, they flogged them with swords, took them prisoner and tied them with ropes. They took the knight's horses with them and picked up the most expensive weapons of the vanquished from the ice as battle trophies.

The well-known historical feature film “Alexander Nevsky” shows scenes that amaze the viewer’s imagination of how the remnants of the knight’s army drowned and went under the ice. According to the director’s script, the spring ice could not withstand the weight of the iron-clad crusader knights and, breaking, buried at the bottom of Lake Peipsi those “evil enemies” who survived the bloody battle.

A number of historical studies also suggest that Russian soldiers allegedly specially sawed the ice in the path of the “iron wedge.” In reality, this is not how things happened at all.

The April ice on Lake Peipsi was still strong enough for the entire mass of thousands of people and horses who came together in battle on a relatively small coastal patch. If the ice had turned out to be fragile by that day, then neither Prince Alexander Nevsky nor the leaders of the knightly army of the Livonian Order would have ever fought such a battle with the transition from the western shore of the lake to the eastern.

This is explained simply. And the Novgorodians, Pskovites, and Estonians who lived along the lake coast knew very well the character of Lake Peipus - the breadwinner. In addition, the matter could not have happened without basic ice reconnaissance of the warring parties.

And yet, a large number of mounted knights and foot bollards, scattering from their pursuers in all directions, drowned in the icy water of Lake Peipsi. Just where, in what place?

A little north of the battle site, the Zhelcha River, quite large and full-flowing in those days, flows into Lake Peipsi. When river water flows into the lake, it loosens the spring ice, making it a real trap in this place for those who come to this place on foot or on horseback. Local residents, as well as on geographical maps, call it Sigovitsa.

That’s where some of the order’s brothers ran in fear of their pursuers, having succumbed to the general panic in the ranks of the knightly army. These were those German knights who found themselves cut off from the direct route of escape to the Sobolichsky shore. In addition, many fugitives, mounted and on foot, drowned in ice holes.

It seems that Prince Alexander Yaroslavich, who always attached great importance to reconnaissance, clarifying enemy positions and reconnaissance of the area, knew well from the words of the indigenous inhabitants about the existence of Sigovitsa and its treachery for humans. Therefore, he covered himself with it from his right flank. The crusader enemy, be it on horseback or on foot, simply could not bypass the Russian army from the north in this case.

Sigowitz with her loose ice on the day of April 5, she guarded the positions of the Russian army from the north better than any, the strongest and most vigilant “watchman”. After all, the Novgorod prince, as a commander, chose the site of the Battle of the Ice himself, on the advice of people who knew these lake shores. I chose well and didn’t make a mistake.

The defeat of the united army of the German order and the Baltic Catholic bishops was complete. In the battle on Lake Peipus, on Uzmen at the Crow Stone on that memorable day for Rus', 400 German knights fell, “and there are countless miracles (that is, bollards).” Some of them died in the battle itself, and the other part - while fleeing from the Russian mounted warriors who were pursuing them. Among those who survived on the Estonian coast there were a large number of wounded.

The losses among the Livonian crusaders were, without a doubt, much greater in number. It’s just that in those distant centuries and later, the calculation of losses was carried out in a rather unique way - ordinary soldiers were simply not taken into account either among the killed and wounded or among the prisoners. The attitude towards noble people was completely different. And besides, the noble knight was at least the leader of a military detachment of several people. That is, he stood at the head of the “spear”. It was quite easy to distinguish a slain knight from an ordinary one. That is why the ancient Russian chronicler kept a record of losses only among the “famous” crusaders.

According to the chronicler, fifty noble knights, whom he calls “deliberate commanders,” were captured. The winners caught them “with the hands of Yash.” The bollard infantrymen were captured “in large numbers” and no one counted them.

Victory in the Battle of the Ice came at a high price. Quite a few warriors and militias fell. The wounded soldiers, under guard, were immediately sent on sleighs to nearby Pskov to be placed in the townspeople’s homes for treatment. Those killed from the battlefield were taken with them. By ancient tradition Most of them were to be buried in their native places - Novgorod, Pskov, villages.

The victorious army did not stand at the site of the Battle of the Ice for long. It left there immediately after the dead and wounded warriors were picked up, prisoners were collected and trophies were taken - weapons, armor. Metal in that distant time was highly valued, and even a broken sword had a good price at a city auction or from a rural blacksmith.

The losses of the German order during the only big battle during the second crusade against Rus' turned out to be simply huge by European standards of the Middle Ages, incredible for knightly wars. Suffice it to say that in the great battle of Brumel in 1119 between the English and French, not counting ordinary soldiers, only three knights were killed. In 1214, not so far from the day of the Battle of the Ice, in another major battle of Bouvines, where the troops of King Philip Augustus of France and the German Emperor Otgon IV decisively fought, the defeated Germans left 70 knights on the battlefield, and the victorious French only three knights. According to some sources, 131 people were captured, according to others, slightly more - 220 people.

Therefore, we can rightfully say that the Battle of the Ice on April 5, 1242 on Lake Peipsi is one of major battles in Europe during the Middle Ages. That's why the battle took its toll historical name- carnage.

If we take into account the ratio of the dead (400) and captured (50) German knights, then it testifies, first of all, to the bloodshed of the Battle of the Ice, the rage of the people who fought in it, and the hatred of the Russian army towards the conquering crusaders. And about the undoubted desire of both to win. Otherwise, there would have been much more prisoners and fewer casualties. History knows many similar examples.

Old Russian chroniclers, praising the victory of Russian weapons won on the ice of Lake Peipsi, unanimously note the special role of Prince Alexander Yaroslavich Nevsky. The authors of the chronicles had no doubt that the Almighty himself stood on his side. “God glorify Grand Duke Alexander here before all the regiments, like Joshua at Jericho,” wrote one of the chroniclers, recalling the times of the Old Testament. He compared the warrior prince with David, who once defeated a giant.

But the most joyful thing for Russian Orthodox people was that there was no one among the enemy commanders equal to Prince Alexander Nevsky. On this occasion, the ancient Russian chronicler writes with undisguised pride: “...And he would never find an opponent in battle.”

In the conditions of the beginning of the Golden Horde yoke on the Russian lands, the people saw an omen of future liberation. The Novgorod prince, who won two brilliant victories on the banks of the Neva River and on the ice of Lake Peipsi, immediately became one of the most famous commanders of his time. Now he had to be taken into account both in the West and in the East. This was an indisputable historical fact.

After the victory in the Battle of the Ice, the name of the prince-commander thundered “across all countries, from the Varangian Sea to the Pontic Sea, and to the Khvalynsky (Caspian) Sea, and to the country of Tiberias, and to the Ararat Mountains...” The Old Russian chronicler, obviously, is not at all here does not exaggerate - the name of Prince Alexander Nevsky, covered with his military glory, has indeed gone far beyond the borders of Russia. That was the glory of a great warrior...

Having won the victory, the Russian army moved across the ice of Lake Peipus towards Pskov. With glory, under the enthusiastic cries of the townspeople, Russian warriors entered the fortress city. Prince Alexander Nevsky rode ahead on horseback, followed by captured German knights on foot. Crowds of captive bollards followed the foot militia, which entered Pskov after the cavalry.

Even when the winning army was approaching the city, crowds of Pskovites came out to meet it. Orthodox abbots and priests carried icons and church banners. Those who meet “before the hail sing the glory of Prince Alexander.” The commander drove straight to the Holy Trinity Cathedral, revered by the townspeople, where a solemn prayer service was served.

In the Pskov Detinets - Krome, standing on a high flat hill at the confluence of the Pskov and Velikaya rivers, Prince Alexander Nevsky addressed the army and townspeople who had gathered at a meeting on the occasion of the victory over the Livonian knights. The commander addressed the audience with a speech:

“The Latin ritari (knights) threatened us with slavery, but they themselves were captured. Our brave warriors punished them for their arrogance and contempt for other peoples. Glory to the warriors of Novgorod, Suzdal, Pskov and eternal memory to those who fell on the battlefield.”

The subsequent words of the Novgorod prince at the quiet meeting became a reproach to the Pskov “gentlemen.” “But the Pskov boyars surprise me,” Alexander Yaroslavich said bitterly, “how they could exchange the freedom of their land for personal earthly goods. Our strength was unshakable in the unity of Novgorod and Pskov. But no, the boyars wanted to become masters, to have a rich treasury and power, but they lost everything - both honor and independence. All of Pskov and the Pskov land were brought under the Livonian yoke. Small children were taken hostage and not released - isn’t this a crime against the people? And many of you, narrow-minded (foolish) Pskovites, if you forget about this even to the great-grandsons of Alexander, then you will become like those Jews (Jews) whom the Lord fed in the desert with manna and fried quail and who forgot about all this, just as they forgot God, who freed them from Egyptian captivity."

With their eyes downcast, the Pskov residents listened to the bitter and fair reproach from the lips of the victorious prince. For the subsequent history of the ancient Russian fortress city, it became a fact that from then on the enemy-conqueror never set foot in Pskov until the 20th century. And such attempts have been made repeatedly.

In honor of the victory over the German order, the Pskovites built the Cathedral of John the Baptist on the ice of Lake Peipsi. It still adorns the city to this day, rising beautifully on the banks of the Velikaya River. The peculiarity of the architecture of this Pskov temple is that it externally repeats the appearance of the Novgorod cathedrals of that time. Thus, the Pskovites, breaking their own traditions of building cathedrals, expressed gratitude to the Novgorod brothers who came to liberate their city from the Livonian knights.

After Pskov, the Russian army headed to Novgorod the Great, whose population rejoiced after receiving news of the “noble” victory. Prince Alexander Nevsky triumphantly entered the free city at the head of the Russian army. The veche bell solemnly buzzed over the Volkhov banks. Thousands of townspeople greeted the winners of the German order.

The Novgorod prince rode into the city on horseback ahead of his squad and militia. Behind him came “regiment after regiment, beating tambourines and blowing trumpets.” Following the army, the wounded “warriors” were transported with all care. Convoys with captured knightly weapons and armor pulled along. There turned out to be so many captured weapons that it could be enough for a whole army of Novgorod land.

The captured crusader knights were led “with shame” under guard through the crowded streets of the free city. As it is said in the Pskov chronicle: “Ov’s huts, and the Ov’s tied their bare feet and led them across the ice.” Apparently, the knights fleeing from their pursuers threw off not only their heavy armor, but also their shoes trimmed with iron.

The ancient Russian chronicler will speak about the triumph of the victorious warriors and the Novgorod people in these words: “The Germans boasted: we will take Prince Alexander with our hands, and now God himself has handed them over to him.” Now the order brothers with bowed, bare heads walked obediently at the stirrup of the prince's horse, reflecting on their future fate...

The victory of the Russian army on the ice of Lake Peipsi reached “all the way to Rome.” The papal circle no longer made plans for new crusades on the lands of Novgorod Rus'. Such thoughts were postponed until for a long time. Only at the very beginning XVII century The Pope will bless the sword of the Polish king Sigismund III for the conquest of Muscovy, which was engulfed in the Great Troubles after the death of Tsar Ivan Vasilyevich the Terrible...

In the summer of the same 1242, the German Baltic knighthood was forced to send “eminent” ambassadors with a petition to Novgorod to conduct peace negotiations. The embassy was headed by the knight Andreas - Andreas von Stirland, who four years later became Landmaster of the Livonian Order and served as high position seven years.

After the crushing defeat on the ice of Lake Peipus, the position of the German order deteriorated sharply, so great were not only the losses in military strength, but also the moral and political losses. The chronicler will say: “God’s ritari (knights) came to Novgorod with a bow to ask for peace: “...What we entered... with the sword, we retreat.” This is what was said in the petition of the Livonian crusading knights, who asked for peace from Veliky Novgorod.

Prince Alexander Nevsky himself wanted peace with the Livonian Order. He understood that the continuation of the war with the German knighthood could complicate the situation of the Russian land, which was just beginning to recover from the destructive Batu invasion. That is why the commander did not go into the depths of Livonia after such a convincing victory and did not begin to conquer its lands. And such a campaign, without a doubt, could have been successful - the army of the German order suffered an unprecedented defeat on the ice of Lake Peipsi.

When the order's embassy came to the banks of the Volkhov, Prince Alexander Yaroslavich was not there at that time. He went to Vladimir to see his father to say goodbye to him. The Grand Duke of Vladimir was summoned by Batu Khan to Golden Horde. In Karakorum, Yaroslav Vsevolodovich will be poisoned from her own hands by the mother of the Great Khan Guyuk.

The boyars of the free city agreed to the peace proposed by the German order. The Novgorod veche made the same decision. According to the peace treaty, the Livonian order swore to renounce all lands that last years captured from Rus' in the Pskov and Novgorod regions, from everything that the crusader knighthood attempted. It renounced Pskov, Luga, Vodya, and ceded to the victors part of the order’s territory, the so-called Latygolla. The Livonians pledged to release all prisoners and child hostages captured on the Pskov and Novgorod lands.

For its part, the knightly embassy asked to release the German prisoners of war. Among them were many noble knights not only from Livonia itself, but also from many German and other lands. This request was respected.

On these conditions, the peace treaty of 1242 was signed “without a prince” between the free city of Novgorod and the Livonian Order. It became possible only thanks to the victory on the ice of Lake Peipsi. Thus, for the first time, a limit was put, albeit only temporarily, to the predatory German invasion of the East along the Baltic coast, which had been going on for centuries.

The boundaries of the order's possessions with Pskov and Novgorod, established around the world in 1242, existed without noticeable changes in subsequent centuries. Until the fall of the predatory Livonian Order in the 16th century under the blows of the Moscow armies of the first Russian Tsar Ivan IV Vasilyevich, nicknamed the Terrible.

The head of the order's embassy managed to meet with Prince Alexander Yaroslavich even before he left for the capital city of Vladimir. Then the Novgorod prince directly told the Livonian ambassador that it was better to have good relations with each other, that it was better to trade than to fight. And he reminded that overseas merchants were always received with honors in the free city.

The meeting with the young Novgorod prince-commander and his reasoning made a huge impression on Andreas von Stirland. Upon returning to Livonia, he will tell his entourage the following: “I have passed through many countries and seen many peoples, but I have not met such a king among kings, nor a prince among princes.” This description of the ancient Russian commander-ruler has reached our time in a handwritten line.

And the Vladimir people led by Alexander Nevsky, on the one hand, and the army of the Livonian Order, on the other hand.

The opposing armies met on the morning of April 5, 1242. The Rhymed Chronicle describes the moment the battle began as follows:

Thus, the news from the Chronicle about the Russian battle order as a whole is combined with reports from Russian chronicles about the allocation of a separate rifle regiment in front of the center of the main forces (since 1185).In the center, the Germans broke through the Russian line:

But then the troops of the Teutonic Order were surrounded by the Russians from the flanks and destroyed, and other German troops retreated to avoid the same fate: the Russians pursued those running on the ice for 7 miles. It is noteworthy that, unlike the Battle of Omovzha in 1234, sources close to the time of the battle do not report that the Germans fell through the ice; according to Donald Ostrowski, this information penetrated into later sources from the description of the battle of 1016 between Yaroslav and Svyatopolk in The Tale of Bygone Years and The Tale of Boris and Gleb.In the same year, the Teutonic Order concluded a peace treaty with Novgorod, abandoning all of its recent seizures not only in Rus', but also in Letgol. An exchange of prisoners was also carried out. Only 10 years later the Teutons tried to recapture Pskov.

Scale and significance of the battle

The “Chronicle” says that in the battle there were 60 Russians for every German (which is recognized as an exaggeration), and about the loss of 20 knights killed and 6 captured in the battle. “Chronicle of the Grand Masters” (“Die jungere Hochmeisterchronik”, sometimes translated as “Chronicle of the Teutonic Order”), the official history of the Teutonic Order, written much later, speaks of the death of 70 order knights (literally “70 order gentlemen”, “seuentich Ordens Herenn” ), but unites those who died during the capture of Pskov by Alexander and on Lake Peipsi.

According to the traditional point of view in Russian historiography, this battle, together with the victories of Prince Alexander over the Swedes (July 15, 1240 on the Neva) and over the Lithuanians (in 1245 near Toropets, near Lake Zhitsa and near Usvyat), was of great importance for Pskov and Novgorod, delaying the onslaught of three serious enemies from the west - at the very time when the rest of Russia was greatly weakened Mongol invasion. In Novgorod, the Battle of the Ice, together with the Neva victory over the Swedes, was remembered in litanies in all Novgorod churches back in the 16th century. In Soviet historiography, the Battle of the Ice was considered one of the largest battles in the entire history of German knightly aggression in the Baltic states, and the number of troops on Lake Peipsi was estimated at 10-12 thousand people for the Order and 15-17 thousand people from Novgorod and their allies (the last figure corresponds to Henry of Latvia’s assessment of the number of Russian troops when describing their campaigns in the Baltic states in the 1210-1220s), that is, approximately at the same level as in the Battle of Grunwald () - up to 11 thousand people for the Order and 16-17 thousand people in the Polish-Lithuanian army. The Chronicle, as a rule, reports on the small number of Germans in those battles that they lost, but even in it the Battle of the Ice is clearly described as a defeat of the Germans, in contrast, for example, to the Battle of Rakovor ().

As a rule, the minimum estimates of the number of troops and losses of the Order in the battle correspond to the historical role that specific researchers assign to this battle and the figure of Alexander Nevsky as a whole (for more details, see Assessments of the activities of Alexander Nevsky). V. O. Klyuchevsky and M. N. Pokrovsky did not mention the battle at all in their works.

The English researcher J. Fennell believes that the significance of the Battle of the Ice (and the Battle of the Neva) is greatly exaggerated: “Alexander did only what numerous defenders of Novgorod and Pskov did before him and what many did after him - namely, rushed to protect the extended and vulnerable borders from invaders." Russian professor I. N. Danilevsky also agrees with this opinion. He notes, in particular, that the battle was inferior in scale to the Battle of Saul (1236), in which the Lithuanians killed the master of the order and 48 knights, and the battle of Rakovor; Contemporary sources even describe the Battle of the Neva in more detail and give it greater significance. However, in Russian historiography it is not customary to remember the defeat at Saul, since the Pskovites took part in it on the side of the defeated knights.

German historians believe that, while fighting on the western borders, Alexander Nevsky did not pursue any coherent political program, but successes in the West provided some compensation for the horrors of the Mongol invasion. Many researchers believe that the very scale of the threat that the West posed to Rus' is exaggerated. On the other hand, L. N. Gumilyov, on the contrary, believed that it was not the Tatar-Mongol “yoke”, but rather Catholic Western Europe represented by the Teutonic Order and the Riga Archbishopric that posed a mortal threat to the very existence of Rus', and therefore the role of Alexander Nevsky’s victories in Russian history is especially great.

The Battle of the Ice played a role in the formation of the Russian national myth, in which Alexander Nevsky was assigned the role of “defender of Orthodoxy and the Russian land” in the face of the “Western threat”; victory in the battle was considered to justify the prince's political moves in the 1250s. The cult of Nevsky became especially relevant during the Stalin era, serving as a kind of clear historical example for the cult of Stalin himself. The cornerstone of the Stalinist myth about Alexander Yaroslavich and the Battle of the Ice was the film by Sergei Eisenstein (see below).

On the other hand, it is incorrect to assume that the Battle of the Ice became popular in the scientific community and among the general public only after the appearance of Eisenstein’s film. “Schlacht auf dem Eise”, “Schlacht auf dem Peipussee”, “Prœlium glaciale” [Battle on the Ice (US), Battle of Lake Peipus (German), Battle of the Ice (Latin).] - such established concepts are found in Western sources long before the director’s works. This battle was and will forever remain in the memory of the Russian people just like, say, the Battle of Borodino, which strictly speaking cannot be called victorious - the Russian army abandoned the battlefield. And for us this is a great battle, which played an important role in the outcome of the war.

Memory of the battle

Movies

Music

- The musical score for Eisenstein's film, composed by Sergei Prokofiev, is a cantata focusing on the events of the battle.

Literature

Monuments

Monument to the squads of Alexander Nevsky on Mount Sokolikha

Monument to Alexander Nevsky and Worship Cross

The bronze worship cross was cast in St. Petersburg at the expense of patrons of the Baltic Steel Group (A. V. Ostapenko). The prototype was the Novgorod Alekseevsky Cross. The author of the project is A. A. Seleznev. The bronze sign was cast under the direction of D. Gochiyaev by the foundry workers of NTCCT CJSC, architects B. Kostygov and S. Kryukov. When implementing the project, fragments from the lost wooden cross by sculptor V. Reshchikov were used.

Commemorative cross for prince "s armed force of Alexander Nevsky (Kobylie Gorodishe).jpg

Memorial cross to the squads of Alexander Nevsky

Monument in honor of the 750th anniversary of the battle

Error creating thumbnail: File not found

Monument in honor of the 750th anniversary of the battle (fragment)

In philately and on coins

Data

Due to the incorrect calculation of the date of the battle according to the new style, the Day of Military Glory of Russia - the Day of the Victory of Russian soldiers of Prince Alexander Nevsky over the Crusaders (established by Federal Law No. 32-FZ of March 13, 1995 “On Days of Military Glory and Memorable Dates of Russia”) is celebrated on 18 April instead of the correct new style April 12. The difference between the old (Julian) and new (Gregorian, first introduced in 1582) style in the 13th century would have been 7 days (counting from April 5, 1242), and the difference between them of 13 days occurs only in the period 03.14.1900-14.03 .2100 (new style). In other words, Victory Day on Lake Peipsi (April 5, old style) is celebrated on April 18, which actually falls on April 5, old style, but only at the present time (1900-2099).

At the end of the 20th century in Russia and some republics of the former USSR, many political organizations celebrated the unofficial holiday Russian Nation Day (April 5), intended to become a date for the unity of all patriotic forces.

On April 22, 2012, on the occasion of the 770th anniversary of the Battle of the Ice, the Museum of the History of the Expedition of the USSR Academy of Sciences to clarify the location of the Battle of the Ice in 1242 was opened in the village of Samolva, Gdovsky District, Pskov Region.

see also

Write a review about the article "Battle on the Ice"

Notes

- Razin E. A.

- Uzhankov A.

- Battle of the Ice 1242: Proceedings of a complex expedition to clarify the location of the Battle of the Ice. - M.-L., 1966. - 253 p. - P. 60-64.

- . Its date is considered more preferable, since in addition to the number it also contains a link to the day of the week and church holidays (the day of remembrance of the martyr Claudius and the day of praise to the Virgin Mary). In the Pskov Chronicles the date is April 1.

- Donald Ostrowski(English) // Russian History/Histoire Russe. - 2006. - Vol. 33, no. 2-3-4. - P. 304-307.

- .

- .

- Henry of Latvia. .

- Razin E. A. .

- Danilevsky, I.. Polit.ru April 15, 2005.

- Dittmar Dahlmann. Der russische Sieg über die “teutonische Ritter” auf der Peipussee 1242 // Schlachtenmythen: Ereignis - Erzählung - Erinnerung. Herausgegeben von Gerd Krumeich und Susanne Brandt. (Europäische Geschichtsdarstellungen. Herausgegeben von Johannes Laudage. - Band 2.) - Wien-Köln-Weimar: Böhlau Verlag, 2003. - S. 63-76.

- Werner Philipp. Heiligkeit und Herrschaft in der Vita Aleksandr Nevskijs // Forschungen zur osteuropäischen Geschichte. - Band 18. - Wiesbaden: Otto Harrassowitz, 1973. - S. 55-72.

- Janet Martin. Medieval Russia 980-1584. Second edition. - Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007. - P. 181.

- . gumilevica.kulichki.net. Retrieved September 22, 2016.

- // Gdovskaya Zarya: newspaper. - 30.3.2007.

- (inaccessible link since 05/25/2013 (2106 days) - story , copy) //Official website of the Pskov region, July 12, 2006]

- .

- .

- .

Literature

- Lipitsky S. V. Battle on the Ice. - M.: Military Publishing House, 1964. - 68 p. - (The heroic past of our Motherland).

- Mansikka V.Y. Life of Alexander Nevsky: Analysis of editions and text. - St. Petersburg, 1913. - “Monuments ancient writing" - Vol. 180.

- Life of Alexander Nevsky / Prep. text, translation and comm. V. I. Okhotnikova // Monuments of literature of Ancient Rus': XIII century. - M.: Fiction, 1981.

- Begunov Yu. K. Monument of Russian literature of the 13th century: “The Tale of the Death of the Russian Land” - M.-L.: Nauka, 1965.

- Pashuto V.T. Alexander Nevsky - M.: Young Guard, 1974. - 160 p. - Series “Life of Remarkable People”.

- Karpov A. Yu. Alexander Nevsky - M.: Young Guard, 2010. - 352 p. - Series “Life of Remarkable People”.

- Khitrov M. Holy Blessed Grand Duke Alexander Yaroslavovich Nevsky. Detailed biography. - Minsk: Panorama, 1991. - 288 p. - Reprint edition.

- Klepinin N. A. Holy Blessed and Grand Duke Alexander Nevsky. - St. Petersburg: Aletheia, 2004. - 288 p. - Series “Slavic Library”.

- Prince Alexander Nevsky and his era: Research and materials / Ed. Yu. K. Begunova and A. N. Kirpichnikov. - St. Petersburg: Dmitry Bulanin, 1995. - 214 p.

- Fennell J. The crisis of medieval Rus'. 1200-1304 - M.: Progress, 1989. - 296 p.

- Battle of the Ice 1242: Proceedings of a complex expedition to clarify the location of the Battle of the Ice / Rep. ed. G. N. Karaev. - M.-L.: Nauka, 1966. - 241 p.

- Tikhomirov M. N. About the place of the Battle of the Ice // Tikhomirov M. N. Ancient Rus': Sat. Art. / Ed. A. V. Artsikhovsky and M. T. Belyavsky, with the participation of N. B. Shelamanova. - M.: Science, 1975. - P. 368-374. - 432 s. - 16,000 copies.(in lane, superreg.)

- Nesterenko A. N. Alexander Nevsky. Who won the Battle of the Ice., 2006. Olma-Press.

Links

An excerpt characterizing the Battle of the Ice

His illness took its own physical course, but what Natasha called: this happened to him happened to him two days before Princess Marya’s arrival. This was the last moral struggle between life and death, in which death won. It was the unexpected consciousness that he still valued the life that seemed to him in love for Natasha, and the last, subdued fit of horror in front of the unknown.It was in the evening. He was, as usual after dinner, in a slight feverish state, and his thoughts were extremely clear. Sonya was sitting at the table. He dozed off. Suddenly a feeling of happiness overwhelmed him.

“Oh, she came in!” - he thought.

Indeed, sitting in Sonya’s place was Natasha, who had just entered with silent steps.

Since she began following him, he had always experienced this physical sensation of her closeness. She sat on an armchair, sideways to him, blocking the light of the candle from him, and knitted a stocking. (She learned to knit stockings since Prince Andrei told her that no one knows how to take care of the sick like old nannies who knit stockings, and that there is something soothing in knitting a stocking.) Thin fingers quickly fingered her from time to time the clashing spokes, and the pensive profile of her downcast face was clearly visible to him. She made a movement and the ball rolled off her lap. She shuddered, looked back at him and, shielding the candle with her hand, with a careful, flexible and precise movement, she bent, raised the ball and sat down in her previous position.

He looked at her without moving, and saw that after her movement she needed to take a deep breath, but she did not dare to do this and carefully took a breath.

In the Trinity Lavra they talked about the past, and he told her that if he were alive, he would forever thank God for his wound, which brought him back to her; but since then they never spoke about the future.

“Could it or could it not have happened? - he thought now, looking at her and listening to the light steel sound of the knitting needles. - Was it really only then that fate brought me so strangely together with her that I might die?.. Was the truth of life revealed to me only so that I could live in a lie? I love her more than anything in the world. But what should I do if I love her? - he said, and he suddenly groaned involuntarily, according to the habit that he acquired during his suffering.

Hearing this sound, Natasha put down the stocking, leaned closer to him and suddenly, noticing his glowing eyes, walked up to him with a light step and bent down.

- You are not asleep?

- No, I’ve been looking at you for a long time; I felt it when you came in. No one like you, but gives me that soft silence... that light. I just want to cry with joy.

Natasha moved closer to him. Her face shone with rapturous joy.

- Natasha, I love you too much. More than anything else.

- And I? “She turned away for a moment. - Why too much? - she said.

- Why too much?.. Well, what do you think, how do you feel in your soul, in your whole soul, will I be alive? What do you think?

- I'm sure, I'm sure! – Natasha almost screamed, taking both his hands with a passionate movement.

He paused.

- How good it would be! - And, taking her hand, he kissed it.

Natasha was happy and excited; and immediately she remembered that this was impossible, that he needed calm.

“But you didn’t sleep,” she said, suppressing her joy. – Try to sleep... please.

He released her hand, shaking it; she moved to the candle and sat down again in her previous position. She looked back at him twice, his eyes shining towards her. She gave herself a lesson on the stocking and told herself that she wouldn't look back until she finished it.

Indeed, soon after that he closed his eyes and fell asleep. He did not sleep for long and suddenly woke up in a cold sweat.

As he fell asleep, he kept thinking about the same thing he had been thinking about all the time - about life and death. And more about death. He felt closer to her.

"Love? What is love? - he thought. – Love interferes with death. Love is life. Everything, everything that I understand, I understand only because I love. Everything is, everything exists only because I love. Everything is connected by one thing. Love is God, and to die means for me, a particle of love, to return to the common and eternal source.” These thoughts seemed comforting to him. But these were just thoughts. Something was missing in them, something was one-sided, personal, mental - it was not obvious. And there was the same anxiety and uncertainty. He fell asleep.

He saw in a dream that he was lying in the same room in which he was actually lying, but that he was not wounded, but healthy. Many different faces, insignificant, indifferent, appear before Prince Andrei. He talks to them, argues about something unnecessary. They are getting ready to go somewhere. Prince Andrey vaguely remembers that all this is insignificant and that he has other, more important concerns, but continues to speak, surprising them, some empty, witty words. Little by little, imperceptibly, all these faces begin to disappear, and everything is replaced by one question about the closed door. He gets up and goes to the door to slide the bolt and lock it. Everything depends on whether he has time or not time to lock her. He walks, he hurries, his legs don’t move, and he knows that he won’t have time to lock the door, but still he painfully strains all his strength. And a painful fear seizes him. And this fear is the fear of death: it stands behind the door. But at the same time, as he powerlessly and awkwardly crawls towards the door, something terrible, on the other hand, is already, pressing, breaking into it. Something inhuman - death - is breaking at the door, and we must hold it back. He grabs the door, strains his last efforts - it is no longer possible to lock it - at least to hold it; but his strength is weak, clumsy, and, pressed by the terrible, the door opens and closes again.

Once again it pressed from there. The last, supernatural efforts were in vain, and both halves opened silently. It has entered, and it is death. And Prince Andrei died.

But at the same moment as he died, Prince Andrei remembered that he was sleeping, and at the same moment as he died, he, making an effort on himself, woke up.

“Yes, it was death. I died - I woke up. Yes, death is awakening! - his soul suddenly brightened, and the veil that had hitherto hidden the unknown was lifted before his spiritual gaze. He felt a kind of liberation of the strength previously bound in him and that strange lightness that has not left him since then.

When he woke up in a cold sweat and stirred on the sofa, Natasha came up to him and asked what was wrong with him. He did not answer her and, not understanding her, looked at her with a strange look.

This was what happened to him two days before the arrival of Princess Marya. From that very day, as the doctor said, the debilitating fever took on a bad character, but Natasha was not interested in what the doctor said: she saw these terrible, more undoubted moral signs for her.

From this day on, for Prince Andrei, along with awakening from sleep, awakening from life began. And in relation to the duration of life, it did not seem to him slower than awakening from sleep in relation to the duration of the dream.

There was nothing scary or abrupt in this relatively slow awakening.

His last days and hours passed as usual and simply. And Princess Marya and Natasha, who did not leave his side, felt it. They did not cry, did not shudder, and lately, feeling this themselves, they no longer walked after him (he was no longer there, he left them), but after the closest memory of him - his body. The feelings of both were so strong that the external, terrible side of death did not affect them, and they did not find it necessary to indulge their grief. They did not cry either in front of him or without him, but they never talked about him among themselves. They felt that they could not put into words what they understood.

They both saw him sink deeper and deeper, slowly and calmly, away from them somewhere, and they both knew that this was how it should be and that it was good.

He was confessed and given communion; everyone came to say goodbye to him. When their son was brought to him, he put his lips to him and turned away, not because he felt hard or sorry (Princess Marya and Natasha understood this), but only because he believed that this was all that was required of him; but when they told him to bless him, he did what was required and looked around, as if asking if anything else needed to be done.

When the last convulsions of the body, abandoned by the spirit, took place, Princess Marya and Natasha were here.

– Is it over?! - said Princess Marya, after his body had been lying motionless and cold in front of them for several minutes. Natasha came up, looked into the dead eyes and hurried to close them. She closed them and did not kiss them, but kissed what was her closest memory of him.

“Where did he go? Where is he now?..”

When the dressed, washed body lay in a coffin on the table, everyone came up to him to say goodbye, and everyone cried.

Nikolushka cried from the painful bewilderment that tore his heart. The Countess and Sonya cried out of pity for Natasha and that he was no more. The old count cried that soon, he felt, he would have to take the same terrible step.